.png)

By Rahul Ghosh

Rahul Ghosh is a banking and risk expert who advises banks, corporates, and central banks, and builds tech solutions for risk management. He authored two books on risk.

September 5, 2025 at 9:07 AM IST

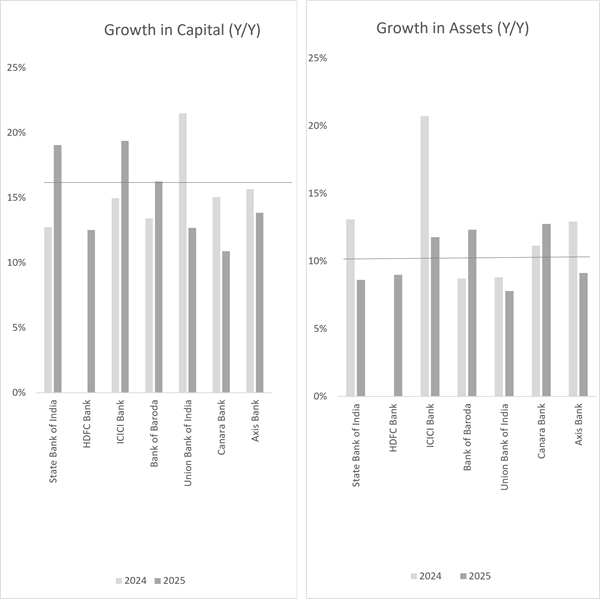

Indian banks have long been comfortably capitalised. Yet in recent years, capital growth has not merely kept pace with assets; it has outstripped it. Average bank assets have expanded at 14% annually over the past two years, but capital has grown at 18%. This divergence signals balance sheets that are not just sound but actively fortified for future expansion.

Capital, in essence, is the buffer that enables banks to withstand losses without endangering depositor funds. Regulatory frameworks, built on Basel standards, determine the precise amount of capital to be held against the risk profile of assets. Risk-free holdings, such as government securities or central bank deposits, require no capital allocation. Riskier exposures such as business loans or unsecured retail credit demand significantly more. The calculus is clear: higher-yielding assets come with a greater capital burden.

Add to this the dimension of time. The Basel ICAAP framework, equally applicable to Indian banks, mandates them to make plans in a way to ensure sufficiency of capital for the next three to five years (three being the norm at present).

Balance Sheet Strength

While the capital adequacy ratio of Indian banks stands at around 17.3%, well above the mandated 11.5%, the pace of capital growth merits closer attention. A review of the country’s seven largest banks by assets shows average asset growth of 10-12% in the last two years, but capital has expanded by about 16% (See Chart). Importantly, this expansion is driven almost entirely by retained earnings, with only a single bank tapping external markets.

Chart by author, based on data from individual bank disclosures

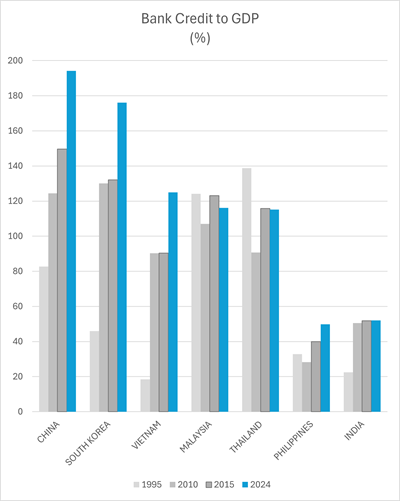

Why then are banks building buffers at such a clip? Let us look at the macroeconomic picture. India is on the cusp of a financing super-cycle. History offers lessons: China, South Korea, and Vietnam all relied heavily on bank-driven credit to turbocharge their growth (See Chart). Their credit-to-GDP ratio doubled within a handful of years, fuelling rapid economic transformation—from 50% to 100% for both South Korea and Vietnam, and China added 30% during an eight-year period. India, at 56% today, still lags behind. This data excludes shadow banks and NBFIs.

Chart by author, based on data from “World Bank Data, World Development Indicators”. For some countries, figure unavailable for 2024, assumed at the level of preceding available year.

The ambitions are clear: a $7.3 trillion economy by 2030, up from just under $4 trillion today. Achieving this will demand a sharp rise in credit penetration, with the credit-to-GDP ratio climbing to at least 80%. That translates into bank lending swelling from $2.2 trillion today to $5.8 trillion by 2030, implying annualised credit growth of 22%. For that to materialise, capital must grow even faster, absorbing regulatory requirements, expected credit losses, and Basel’s forward-looking ICAAP mandates.

Profits, then, become the fulcrum of this story. Capital augmentation in India has so far been driven by retained earnings, but profitability is uneven across banks. While some consistently generate robust surpluses, others will struggle to sustain the pace. On current trends, the sector as a whole faces a potential shortfall of over $200 billion by 2030.

This is not to sound alarmist. Banks are not entering this decade from a position of weakness. Quite the opposite: their balance sheets are muscular, provisions are high, and asset quality has improved markedly. But the question is one of trajectory. If credit expansion is to underpin India’s growth leap, capital must not only remain ample, but also continue to outpace asset growth.

The current surge in capitalisation shows encouraging foresight, but the sustainability of this trend is less assured. Some institutions will likely end up with surpluses, others with deficits. Managing this divergence, while preserving the stability that has been so painstakingly built, will be the real test. Reliance solely on internal accruals may prove insufficient; unless capital is managed more efficiently, external infusions could become unavoidable.

The capital buffers Indian banks are building today are not incidental. They are preparation for a future in which India’s growth ambitions depend more heavily than ever on credit. The next question, to be tackled in the following part of this three-part series, is how banks can bridge the projected capital gap without compromising either profitability or prudence.

*This article is the second in a three-part series. The first part examined if Indian banks can sustain their capital strength and the final article will explore how capital can be raised from existing resources.