.png)

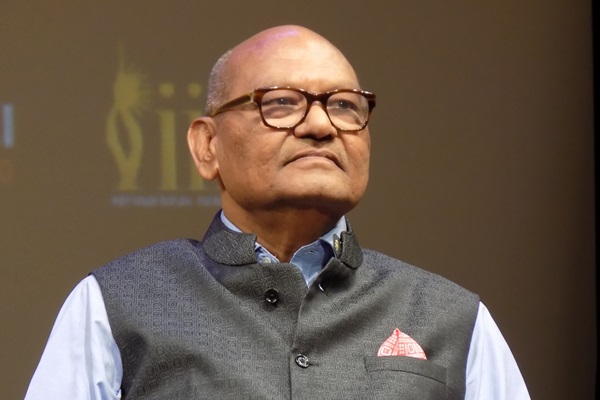

Gurumurthy, ex-central banker and a Wharton alum, managed the rupee and forex reserves, government debt and played a key role in drafting India's Financial Stability Reports.

December 23, 2025 at 5:48 AM IST

Markets are exceptionally good at pricing fear. They are far less competent at pricing relief, especially the relief that does not arrive with a crisis, a crash, or a central bank rescue package attached.

That is why the most interesting question around a hypothetical end to the Russia–Ukraine war is not whether equities would rally, gold would fall, or currencies would lurch reflexively. Those outcomes are easy, visible, and likely short-lived. The real question is whether markets are underpricing a set of pleasant uncertainties… outcomes that are neither guaranteed nor dramatic, but which carry asymmetric upside precisely because they lack narrative force.

There may be more of them than is currently acknowledged.

Macroeconomic thinking treats peace as a slow variable. Wars end, but scars persist. Trade normalises grudgingly. Capital tiptoes back. Trust rebuilds over years. This bias is understandable. Ceasefires fail. Sanctions linger. Geopolitics rarely resets cleanly.

But this war has frozen an unusually large share of global economic plumbing: energy flows, payment systems, shipping insurance, commodity finance, even reserve assets. If peace were to arrive not merely as a ceasefire, but as a coordinated easing of sanctions and even partial release of frozen assets, the response need not be linear.

Capital hoarded defensively—cash, gold, short-duration bonds, inert hedges—does not reallocate politely. It moves when uncertainty collapses. Corporate investment plans shelved for lack of visibility do not restart incrementally; they restart when financing terms become predictable and policy risk recedes.

Markets, adept at extrapolating stress, may be underestimating how quickly uncertainty itself can compress.

For decades, macro intuition rested on a simple rule: a weaker dollar signalled US recession, financial stress, or fiscal panic. That relationship has already broken down.

In recent episodes, the dollar has softened despite the US economy performing strongly; resilient consumption, heavy AI-led capital expenditure, robust growth, and equity markets near highs. This is not an anomaly. It reflects a shift in what the dollar has been pricing.

In the past, the dollar has functioned less as a proxy for US growth and more as a global insurance instrument, a hedge against escalating geopolitical risk, sanctions uncertainty, and systemic fracture. Its prior strength was not merely about American outperformance, but about rising global fear.

Does the recent softening, therefore, imply that the dollar has lost this role? Or does it suggest that the marginal demand for that insurance is fading?

The underpriced outcome, however, may not necessarily be a much weaker dollar. Mean reversion risks remain real, and US growth still dominates globally. What markets appear to underprice instead is a less volatile, less weaponised dollar—one that trades within a narrower range as geopolitical hedging demand recedes.

Markets are far better at pricing direction than they are at pricing volatility regimes. A stable dollar is not dramatic, but it is profoundly enabling for trade, capital flows, and emerging-market policy autonomy.

Emerging markets perform best not when the US is weak, but when the US is strong and the rest of the world is allowed to grow.

A credible peace settlement, combined with tariff de-escalation and lower energy volatility, creates precisely that environment. Risk premia compress quietly. Currencies stabilise without central banks panicking. Equity multiples expand not because liquidity floods in, but because earnings visibility improves.

India’s upside, in particular, may come less from spectacle and more from the absence of shocks. Stable energy imports, predictable fertiliser supplies, eased trade frictions, and lower commodity volatility do not make headlines. But they reduce inflation surprises, simplify fiscal arithmetic, and allow monetary policy to operate without constant firefighting.

Markets tend to undervalue this kind of stability because it lacks narrative drama. Yet it is exactly what supports long-term equity valuations and patient capital.

The reflexive trade around peace is straightforward: sell gold. That instinct is probably correct, at least initially. Gold has thrived on war risk, sanctions anxiety, and institutional distrust.

But hedging does not disappear; it migrates.

Many commodities already trade at elevated levels. Energy and defence-linked inputs have repriced structurally, and supply remains constrained by years of capex discipline. Peace does not necessarily collapse these markets. Instead, it compresses risk premia, stabilises demand planning, and improves cash-flow visibility.

The underpriced element is not explosive upside in spot prices, but duration—the likelihood that commodity-linked cash flows remain viable for longer. Peace reduces left-tail risk, lowering the probability of abrupt demand collapses, policy shocks, or disorderly price reversals. It allows industrial users to hedge usage rather than fear. That asymmetry shows up less in commodities themselves and more in the equities and balance sheets built around them.

Markets, trained to think in binaries, risk-on versus risk-off, are slow to price this middle state.

Soft Landing

The dominant fear in US equities is that a correction in mega-cap technology must drag the entire market down. That assumption confuses leadership concentration with index fragility.

A more plausible and underpriced outcome is a rotational soft landing. Mega-cap technology corrects through time rather than price. Earnings grow while multiples compress gradually. Traditional sectors such as industrials, energy, defence, materials, and financials could absorb marginal leadership.

The index goes sideways, but its internals might change completely.

This is not unprecedented. Versions of it played out in the mid-2000s and intermittently after 2013. What makes it plausible now is that traditional sectors finally have macro support: infrastructure spending, precautionary defence budgets, disciplined energy capex, and stable nominal growth.

Again, this is not a case for optimism about outcomes. It is a case that markets are overpricing uncertainty and underpricing the collapse of variance when risks diminish at the margin.

Markets are excellent at pricing disaster and slow to price relief. They extrapolate recent pain longer than necessary and demand excessive proof before accepting that uncertainty has diminished.

If peace arrives in a credible form, the obvious trades will happen quickly and fade just as fast.

What may take longer to register are the quieter effects—steadier currencies, more predictable commodity businesses, and markets adjusting through rotation rather than collapse.

These outcomes are not guaranteed.

But because markets rarely price them well, they offer asymmetric returns.