.png)

Groupthink is the House View of BasisPoint’s in-house columnists.

February 18, 2026 at 12:32 PM IST

As bond yields cool after the turbulence of December and January, it may be tempting to assume that liquidity conditions have fully normalised. A closer reading of money-market behaviour suggests that the underlying issue was not duration stress alone arising from large long-term bond issuances by the Centre and states, but fragile funding conditions at the short end of the curve that also saw CP and CD rates surge.

The Reserve Bank has since injected substantial liquidity into the system.

In December and January, it conducted OMO purchase auctions totalling ₹3.5 trillion, two 90-day variable-rate repo operations totalling ₹1.365 trillion, and long-term foreign-exchange buy-sell swaps totalling $15.1 billion. This was followed by an additional ₹500 billion in OMOs and $10 billion in swaps this month. Taken together with the CRR cut earlier, the cumulative liquidity infusion so far in 2025-26 has reached ₹11.16 trillion.

Balances in the Standing Deposit Facility, which soaks up excess liquidity, are now close to ₹4 trillion.

Yet the subject of interbank liquidity is not a settled one.

The debate is not whether liquidity is in surplus or shortage at a given moment. The question is whether the structural reserve base is aligned with the scale of credit intermediation that the system is attempting to sustain.

Is the yield curve in line with the monetary policy setting?

Structural Liquidity

The high balances in SDF, the fall in the weighted average call money rate to below the repo rate, and the absence of VRRR auctions to align the call rate with the policy repo rate suggest temporary overcompensation rather than a settled equilibrium.

Come April, the liquidity situation might change again due to pending state and central government borrowings and payment of the last instalment of advance taxes, all of which could drain over ₹5 trillion in March. RBI Governor Sanjay Malhotra had earlier promised that the central bank would be pre-emptive in its liquidity infusions. March is likely to see more bond purchases by the RBI.What banks may, however, want is for the RBI to also recognise and address structural liquidity issues so that monetary policy setting and the yield curve are aligned, or it eases the pain of fiscal dominance.

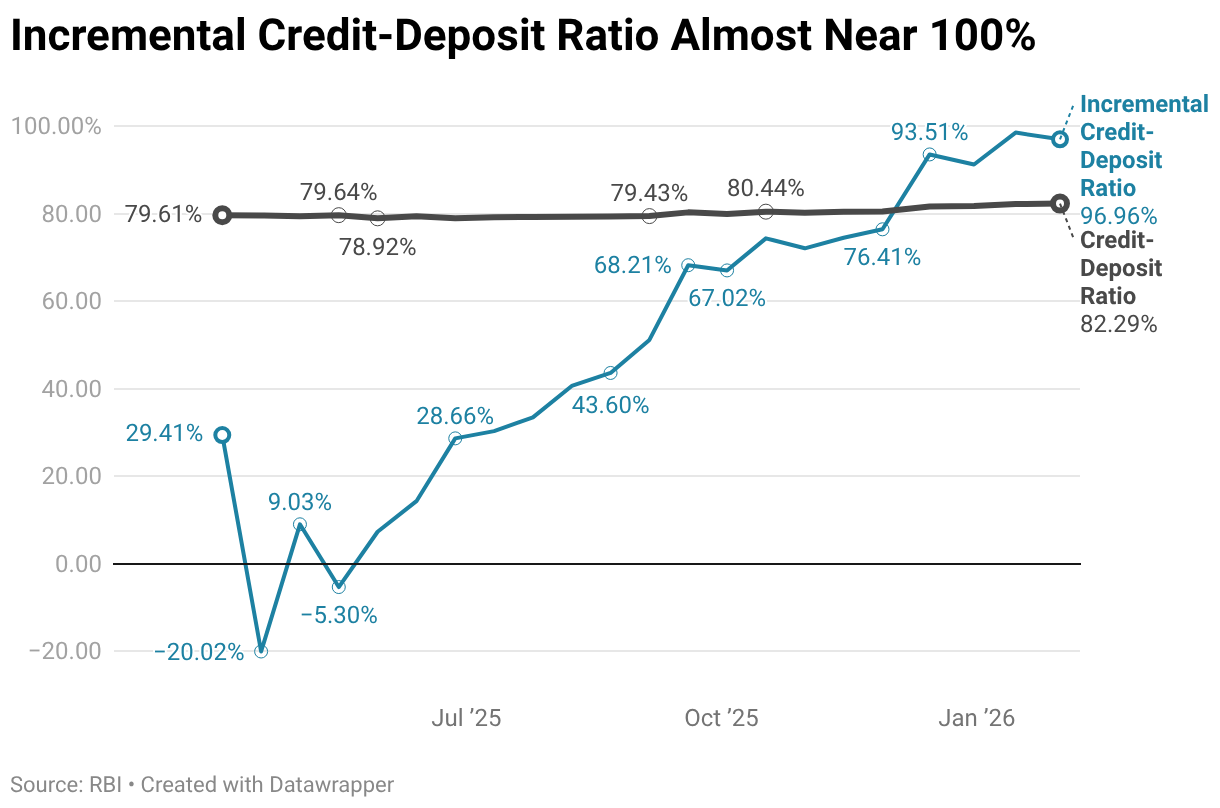

The year-on-year reserve money growth stood at 5.8% at end-January, while broad money expanded 12%. Credit has risen 12.2% so far in 2025-26 and 14.2% year on year as of January 31, whereas deposits increased 10.2% in the financial year and 12.5% year-on-year.

The incremental credit-deposit ratio has approached 97–98%, levels last seen in 2023-24, leaving limited balance-sheet slack for banks.

The takeaway may be that credit expansion is stretching balance sheets faster than the reserve base is expanding, limiting banks’ ability to absorb volatility and weakening the transmission of monetary easing across tenors.

Currency in circulation growing around 11% by the end of last month, which is the fastest pace since mid-2021. Part of this reflects precautionary cash preference, and bankers note that sections of the informal economy have reverted to physical currency after heightened scrutiny of digital transactions. Whatever the motivation, cash leakage reduces the reserve base available for bank deployment.

A multiplier of around six, although steady for some years, means that a relatively modest reserve base is supporting a large stock of deposits and credit. When reserve money expands materially more slowly than credit, liquidity conditions become increasingly dependent on how far banks can stretch their balance sheets rather than on the comfort of base money growth.

In that configuration, the constraint is not the aggregate supply of money; it is the thinness of deployable reserves available to absorb volatility or address funding stress.

When structural reserve growth lags credit expansion so much, monetary easing may work visibly at the overnight margin, but its transmission into longer-duration funding costs becomes uneven. Short-end rates respond; term premia remain sticky.

High bond yields in relation to the monetary easing effected in the last year are a testament to the challenges with transmission. Evidently, long-term government bond yields are higher than long-term home loan rates.

Long-term government bond yields reflect not only the expected policy rate path and supply dynamics but also the market’s assessment of durable liquidity conditions.

When reserve expansion appears episodic rather than structural, duration pricing may incorporate uncertainty over future funding conditions, limiting full compression of term premia even in a benign inflation setting.

Deposit behaviour reinforces the structural nature of the problem. Household financial savings have declined to about 6% of GDP in 2024-25, down from levels before the pandemic, and bank deposits accounted for roughly 4% of GDP.

Financialisation has broadened investment options, reducing the automatic flow of savings into core deposits. Even when deposit growth remains in double digits, it no longer adjusts proportionately to credit expansion in the way it once did, leaving the system with less funding flexibility.

The RBI does not officially target monetary aggregates anymore since it chose inflation targeting over a multi-indicator approach, but base money calculus requires fresh attention to address the challenges of structural liquidity.

Frictional Liquidity

Governor Malhotra hinted at a press conference last year that the RBI aims to maintain surplus liquidity of about 1% of net demand and time liabilities, roughly ₹2.5 trillion. In practice, banks prefer to hold an additional ₹600 billion–₹800 billion as internal buffers and are reluctant to access the marginal standing facility except at the margin.

The effective surplus required for system-wide ease is therefore closer to ₹3.25 trillion. This gap explains why liquidity can appear adequate in aggregate while conditions feel tight in the interbank market.

Another debate centres on the RBI’s renewed preference for the weighted average rate of the thinly traded call money as the operating target over secured overnight rupee rate-based targeting, which has more participants via a collateralised borrowing mechanism.

The deeper question is whether alignment at the overnight point, whether via weighted average rate of the thinly traded call money or secured overnight reference rate, is sufficient to anchor funding conditions across the broader short end of the curve, especially when liquidity demand is segmented across tenors.

Liquidity positions at the overnight point are not percolating across the curve. Would more continuous-term repo operations better address the gaps? Should the RBI not have abandoned the 14-day operations?

Separately, would it be possible for the RBI to maintain a liquidity surplus at 1% of deposits, alongside the additional ₹600 billion–₹800 billion buffer banks prefer, and still target the overnight at the prevailing repo rate?

The government cash balances further complicate liquidity management. At the end of December, balances stood at ₹3.53 trillion, a substantial portion of which represents state government funds parked in non-marketable Treasury bills or through non-competitive bids at T-bill auctions. These resources remain outside the active banking circuit until states or the Centre (to the extent of their portion) spend them. The effect is to withdraw depth from the interbank market and amplify short-end volatility.

If one squares out the math: the RBI injected ₹11.1 trillion so far in 2025-26; around ₹4 trillion is in the Standing Deposit Facility, government cash balances exceed ₹3.5 trillion, and currency leakage accounts for another ₹4 trillion.

Despite the RBI’s operations and balance sheet being the money centre for banks and markets, all the liquidity play is at the shorter end, while longer-end yields remain elevated. The distribution of liquidity across the term curve remains uneven.

Stabilising the overnight rate cannot fully offset structural reserve thinness. Without durable base expansion, transmission across the curve remains partial, and term premia resist compression.

The RBI will need to reassess its liquidity management.

Savings Cover

Households currently save roughly 6% of GDP in financial assets, and India attracts on a net basis around 1% of GDP to fund its current account deficit. This pool of financial savings is largely absorbed by the Centre and states’ borrowings. The corporate sector is left with limited residual financial space, making monetary expansion the residual adjustment mechanism.

Fiscal dominance, inflationary pressures, asset-price distortions, and credit quality are the attendant risks of the central bank's more aggressive balance-sheet expansion.

Should the RBI still look at expanding base money more durably?

The policy trade-off is not trivial. Expanding reserve money through open market operations or foreign exchange swaps would strengthen structural buffers, yet it could interact with capital flows and asset prices in ways that complicate macro management.

Relying predominantly on repo support may stabilise conditions episodically, but it does not resolve the underlying arithmetic of reserve growth. Banks require more durable liquidity, not just collateralised access.

In a system where savings patterns are shifting, and balance sheets are stretched, structural liquidity management requires clarity on how much durable reserve expansion is necessary to align credit growth, compress term premia and transmit policy intent into bond yields.