.png)

Krishnadevan is Editorial Director at BasisPoint Insight. He has worked in the equity markets, and been a journalist at ET, AFX News, Reuters TV and Cogencis.

January 23, 2026 at 5:03 AM IST

India has spent over 10 years building market infrastructure and calling it financialisation. Demat accounts, mobile trading, instant onboarding, SIPs, ETFs and direct mutual funds have scaled at extraordinary speed.

What has lagged, as the SEBI Investor Survey 2025 quietly shows, is the inability of investors to stand in one’s own way. Most countries try to build investor temperament before they scale financial markets. India did it the other way around and hoped behaviour would catch up.

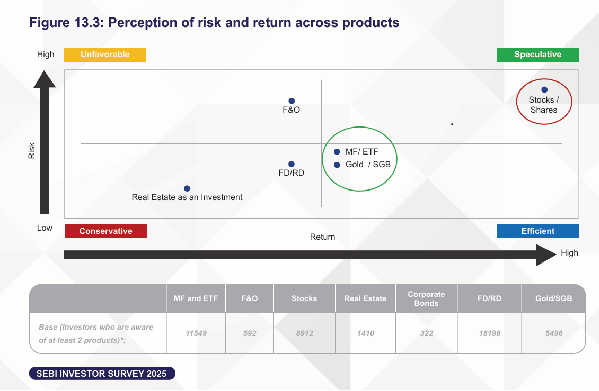

On paper, Indian households appear deeply conservative, with nearly 80% saying they prefer risk-free returns. Fixed deposits, gold and insurance still dominate savings. But that conservatism is more conditional than it looks. When markets rally, the same investors rush into equities, open demat accounts and rediscover the virtues of compounding.

The SEBI survey puts hard numbers on this gap. About 63% of Indian households, roughly 213 million, are aware of at least one securities market product. Only 9.5% actually participate. Awareness has spread. Conviction has not.

Securities Market Penetration by town-classes:

| Incidence | Overall | Urban vs Rural | Urban Town Class | Rural Town Class | |||||

| Urban | Rural | Top 9 | 10-40L | 5-10L | <5L | More than 2500 | Less than 2500 | ||

| Overall Securities Products |

9.5 | 15 | 6 | 23 | 16 | 14 | 10 | 6 | 5 |

*Base = 91950 (all India households, Listing sample - Investor Survey 2025

Urban India looks financially sophisticated, but the picture changes fast outside big cities. About 15% of urban households invest in securities markets, compared with barely 6% in rural India. In the top nine metros, participation rises to around 23%. Financial risk-taking, in other words, is still a city phenomenon.

Behavioural finance terms this loss aversion. People feel losses roughly twice as strongly as equivalent gains. In India, this bias is amplified by cultural memory. Capital protection has long been treated as a financial virtue. Fixed deposits became not just savings tools, but psychological insurance.

Structural Gaps

In developed markets, behavioural bias sits on top of deep structural support. Pension systems force long-term equity ownership. Default retirement flows keep money invested regardless of sentiment. Institutional capital absorbs retail panic.

India lacks that ballast. Mutual funds, insurers and pension funds do provide stabilising flows, but these remain discretionary and closely tied to retail sentiment. There is no mandatory household channel into equities, no system-wide default long-term investing, and no deep culture of automatic retirement allocation.

The result is sharply pro-cyclical behaviour. Investors enter late and exit early. They buy when volatility is low and sell when it rises. Emotionally, this feels rational. Financially, it is exactly backward.

When markets fall, investors do not experience it as a statistical drawdown but as personal failure. The portfolio becomes a reminder of poor judgement. Monthly SIP debits start to feel like repeated mistakes.

SEBI’s survey captures this fragility. Among existing investors, only about 36% report having good knowledge of securities markets. Post-investment challenges are dominated by fears around losses, volatility and wrong decisions. Lower-than-expected returns affect 42% of investors. Uncertainty about whether to stay invested or exit troubles 39%.

People stop SIPs not because they doubt compounding, but because continuing feels emotionally intolerable. Among investors who have gone dormant, about 40% fall into this category, with poor performance cited by 87% as the primary reason.

Bear markets act as identity shocks. The investor persona dissolves and the saver mentality returns. This is not just a knowledge problem. It is a temperament problem and also a safety-net problem. For households with no pension, patchy insurance and volatile income, exiting equities at the first sign of trouble is capital preservation.

Even among those already in markets, risk tolerance remains low. About 71% of stock investors prioritise capital preservation over growth. For mutual fund and ETF investors, that figure rises to 74%.

Fintech platforms reduced friction, but they also sped up emotional reactions. Easier access encouraged activity over patience. More trading often magnifies biases rather than improving behaviour. While 8.5% of households hold demat accounts, 38% of those accounts are dormant.

India’s financialisation story is therefore incomplete. The country has built world-class financial infrastructure, but behavioural capital has not kept pace.

Before investing, 91% of investors cite risk and uncertainty as their primary challenge. After investing, 73% still struggle with the same concerns. Among those who exit markets entirely, poor performance dominates the reasons, with changes in personal goals and costs close behind.

The irony is that the hardest part of investing is not choosing what to buy. It is staying invested once you have. Long-term returns depend less on asset allocation and more on emotional consistency. The real edge is not stock selection, but the ability to stay invested when staying invested feels irrational.

Structural guardrails can help. Default equity exposure in retirement products, auto-escalation of contributions and rule-bound rebalancing can turn inertia into an ally. When the system keeps money invested by design, panic has less room to dictate timing.

Among non-investors who are aware of securities products, 22% intend to invest within the next year, much of that from younger and rural households. That potential matters only if it survives the first contact with market volatility.

Bull markets create investors. Bear markets test whether they were real. What will decide who passes that test will not be the next app, the next product or the next slogan, but whether India can upgrade not just its market infrastructure, but its emotional infrastructure.