.png)

Pakistan, Gaza, and the Strategic Burden of Unmandated Peacekeeping

In 2003, following the US-led invasion of Iraq, New Delhi was approached to deploy an Indian Army brigade for stabilisation duties. One of the brigades under consideration was based in Ranchi. However, the proposal was withdrawn when it became clear that this was not an UN-mandated operation.

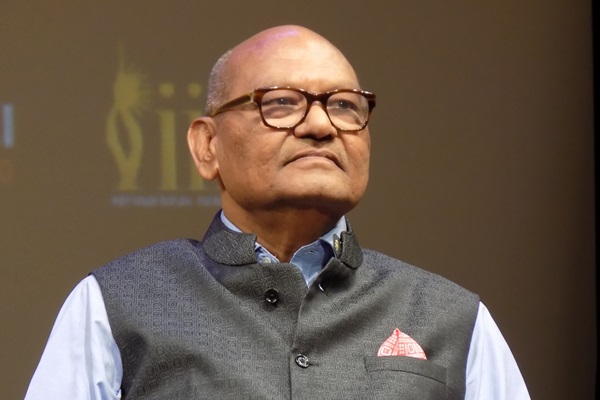

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain is a former Commander of India’s Kashmir Corps and Chancellor of the Central University of Kashmir.

December 23, 2025 at 7:28 AM IST

Reports that Pakistan may be asked to deploy troops for a peacekeeping or stabilisation role in Gaza have drawn global attention. On the surface, the proposition appears logical. Pakistan possesses one of the largest standing armies in the Muslim world, has extensive combat experience, and remains among the most consistent contributors to United Nations peacekeeping operations. Yet history suggests that professional competence alone does not determine the success of such missions. Legitimacy, mandate, political clarity, and exit pathways matter far more. On these counts, Gaza presents deeply troubling uncertainties.

The distinction between peacekeeping and peace enforcement is not academic. Peacekeeping presumes consent, neutrality, and a defined political framework—however fragile. Peace enforcement operates in the absence of these conditions and relies on coercion to impose order. The latter extracts far higher costs, both operationally and politically. Gaza today fits uncomfortably into the second category.

There is a relevant historical parallel from India’s own experience. In April 2003, following the US-led invasion of Iraq, New Delhi was approached to deploy an Indian Army brigade for stabilisation duties. The Indian Army, with a distinguished record in UN missions across Somalia, Cambodia, Lebanon and elsewhere, was institutionally receptive. One of the brigades under consideration was based in Ranchi, and senior officers were informed by the Military Secretary’s Branch to be prepared for short-notice movement.

As deliberations progressed, however, a decisive distinction became clear. This would not be an UN-mandated operation. There would be no blue beret, no international consensus, and no neutral legal framework. The force would operate under an American command structure, inheriting the political baggage of the invasion. Political and military leadership in India converged on the view that operational excellence could not offset the absence of legitimacy. The proposal was withdrawn.

Subsequent events in Iraq vindicated that restraint. Coalition forces, despite overwhelming technological superiority, found themselves mired in asymmetric warfare, targeted by improvised explosive devices and suicide bombers, and drawn into sectarian fault lines they could neither control nor resolve. Stabilisation became elusive. Casualties mounted, public support eroded, and the mission lost coherence.

Somalia offers another cautionary example. What began as a humanitarian intervention under international auspices deteriorated into mission creep and strategic miscalculation, culminating in a US withdrawal that underscored the limits of military power in politically fragmented environments. Both Indian and Pakistani contingents performed professionally during that mission; the failure lay not with the soldiers, but with flawed political assumptions.

It is important to acknowledge that India’s peacekeeping record is exceptional and Pakistan’s is not far behind. Both armies have repeatedly demonstrated discipline, restraint, and adaptability under UN mandates. But Gaza is not a conventional peacekeeping environment. It is one of the most densely populated and politically polarised territories in the world, saturated with armed actors and shaped by decades of unresolved conflict.

Any external force entering Gaza would confront a battlespace unlike most previous missions. Tunnel networks, subterranean logistics, concealed command posts, and the deliberate embedding of military infrastructure within civilian areas negate conventional advantages. Tunnel warfare, in particular, erodes perimeter control, complicates force protection, and blurs the distinction between combatant and civilian space. Even the most capable armies struggle in such environments without escalating civilian harm—an outcome that rapidly erodes legitimacy.

Compounding this is the absence of a functioning political interlocutor. Peacekeeping operations historically rely on at least a minimal political architecture: a recognised host authority, a ceasefire mechanism, or an agreed transitional framework. Gaza currently offers none of these in coherent form. Authority is fragmented and inseparable from armed capability. In such circumstances, external forces are inevitably drawn into arbitration and coercion, becoming de facto enforcers rather than neutral stabilisers. Somalia and Iraq followed this trajectory. Gaza shows similar indicators, amplified by geography and density.

From Pakistan’s perspective, the risks are not confined to the battlefield. The assumption that Islamic identity will confer neutrality or safety is questionable. Modern conflicts have repeatedly demonstrated that cultural or religious affinity does not guarantee acceptance; in some cases, it sharpens perceptions of betrayal or collaboration. Once casualties occur—and they almost certainly will—the domestic narrative becomes as consequential as the operational reality.

Any assessment must also account for leadership calculus. Field Marshal Asim Munir operates amid economic fragility, political contestation, and Pakistan’s growing dependence on external support. Alignment with Washington, particularly with President Trump, offers not merely diplomatic engagement but a form of strategic patronage. Gaza, in this context, becomes a form of currency—an opportunity to reinforce relevance and secure backing.

This introduces a divergence between institutional interest and leadership interest. What may deliver short-term external validation does not necessarily align with the long-term cohesion, morale, or credibility of the Army as an institution, nor with national stability. History suggests that when armies are deployed primarily to sustain patronage rather than serve a clearly defined national interest, operational risks are often underweighted and exit options steadily disappear.

The consequences of failure would not remain confined to Gaza. A prolonged or visibly unsuccessful deployment could generate turbulence within Pakistan itself—political, societal, and institutional. Casualties incurred under a contested mandate are difficult to absorb in a country already under economic stress and political polarisation. Questions would inevitably arise not just about the mission, but about the judgment that authorised it. For an army that has long projected itself as the ultimate stabilising institution of the state, external entanglements that rebound internally carry particular danger.

Pakistan has, in the past, shown strategic restraint in similar circumstances. In 2015, when Saudi Arabia sought Pakistani troop participation in the Yemen conflict, the then Army Chief, General Raheel Sharif, recognised the risks of being drawn into a sectarian, open-ended war with no credible exit strategy. Despite strong external pressure and longstanding ties, Pakistan declined combat involvement. That decision proved prescient. Yemen became a prolonged humanitarian and strategic disaster, ensnaring participants without delivering stability. The contrast with Gaza today is instructive.

From the American viewpoint, memories of past cooperation—particularly in Somalia—may shape present calculations. Pakistan is seen as willing, capable, and politically aligned at a time when few states are prepared to deploy troops. Yet willingness should not be mistaken for wisdom. The absence of a UN mandate raises a fundamental question: who defines success, who sets rules of engagement, and who bears responsibility when outcomes fall short?

History suggests that armies do not fail in such missions because they lack courage or competence. They falter because political objectives are ambiguous, legitimacy is contested, and success is defined by others. Gaza offers no clear endpoint, no universally accepted mandate, and no neutral operating space. For any external force, these are structural vulnerabilities, not manageable complications.

India’s restraint in 2003 reflected an understanding that some missions extract more than they offer, however attractive they may appear in the short term. That judgment has aged well. Pakistan now confronts a comparable moment of choice. The central question is not whether it can deploy troops to Gaza, but whether doing so advances peace or merely postpones instability while transferring its burdens onto soldiers in uniform.

In conflicts shaped by tunnel warfare, fractured authority, and unresolved politics, legitimacy is not an accessory to force—it is its foundation. Where that foundation is absent, peacekeeping becomes an aspiration rather than an outcome, and history is rarely kind to such ventures.