.png)

Rudra Sensarma is a Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Management Kozhikode.*

August 30, 2025 at 5:35 AM IST

The Reserve Bank of India has often faced criticism for being ‘behind the curve’ in its monetary policy actions. In 2022, it was faulted for raising the repo rate too late when inflation was surging above the medium-term target. By the second half of 2024, it was blamed for not cutting the repo rate, even as disinflation had set in.

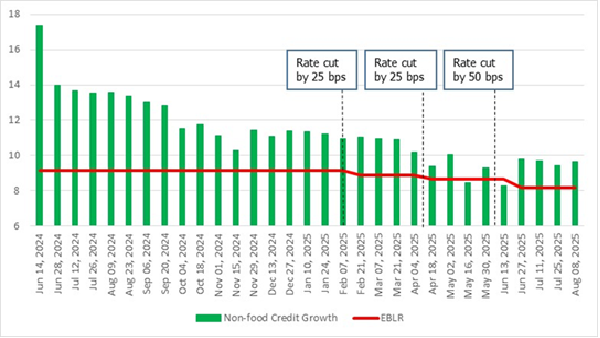

This year, however, the RBI has taken a more aggressive stance, delivering three consecutive repo rate cuts in February, April and June. Yet, these moves have not translated into stronger bank credit growth or improved corporate profitability. Is this a case of ‘too little, too late’, or will monetary policy prove prescient this time? To answer that, we must first look at bank lending rates and credit growth, which are key to the economy’s fortunes.

Banks have responded to the policy rate cuts by reducing their lending rates. The externally benchmark-based lending rate of the State Bank of India has fallen from 9.15% before the policy easing cycle to 8.15% in June – a full pass-through of the cumulative repo rate cut of 100 basis points this year. The average marginal cost of funds-based lending rate of five major banks has declined more modestly from 8.3% in January to 8% in August, reflecting its slower reset mechanism and smaller share in loan books compared to the EBLR.

Despite these rate reductions, credit growth has remained stubbornly weak. Non-food credit of banks grew by 19% in 2023–24 but slowed to 12% in 2024–25, with a sharp slowdown since April–June 2024. Even after the ‘bazooka’ repo rate cut by 50 bps in June, credit growth has hovered at only 8–9% over the subsequent five fortnights. The credit-deposit ratio of banks remained stagnant at around 77–79 throughout this period.

On the supply side, there appears to be little constraint. Banks’ balance sheets are healthier than they have been in decades. The RBI’s Financial Stability Report of June shows gross and net non-performing asset ratios in March 2025 at multi-decadal lows of 2.3% and 0.5%, respectively. Capital buffers remain strong, with the overall capital adequacy ratio at 17.3% and the Tier-1 (core) capital ratio at 14.7%. Profitability indicators also remain robust, in spite of a marginal decline owing to higher cost of funds compared to 2023–24, with net interest margin at 3.5%, return on equity at 13.6% and return on assets at 1.4% at the end of 2024–25. The RBI’s macro stress tests confirmed that banks are resilient even under adverse scenarios.

Why are healthy and profitable banks not able to generate higher credit growth on the back of lower lending rates? The real obstacle lies in demand for credit, not supply. If we turn towards industry’s demand for loans, it is the real interest rate – the quoted rate net of inflation – that reflects a borrower’s true cost of funds. The fall in inflation over the last nine months has meant that real interest rates have actually gone up. For instance, the real interest rate for SBI’s borrowers at the EBLR stood at 4.9% in January — 9.15% minus inflation of 4.26% — but went up to 6.6% by July — 8.15% minus inflation of 1.55%, even though the quoted EBLR rate declined.

Higher real cost of debt naturally dampens firms’ appetite for loans. Meanwhile, investment demand is subdued. The RBI’s quarterly survey of manufacturing companies, the OBICUS survey, shows capacity utilisation inching up only marginally — the seasonally adjusted capacity utilisation rate rose from 75.3 in the third quarter of 2024–25 to 75.5 in the fourth quarter. Order book growth slowed to 7.4% from 8.6% over the same period. Finished goods inventory improved marginally but raw material inventory fell. Although we do not have comparable data for the current quarter yet, these figures are indicative of a lack of interest from industry in ramping up capacity due to weakness in future revenues.

Early data from the first quarter of 2025–26 confirm the tepid trend. The RBI’s latest data on the performance of listed private non-financial companies show that their sales increased 5.5% year-on-year during the first quarter of 2025–26, compared with 7.1% growth in the previous quarter. Operating profit growth of manufacturing and non-IT services companies moderated to 6.9% and 11.3%, respectively, in the same quarter. Consequently, operating profit margins moderated or remained stable.

The industry outlook shows that it will take more than the three repo rate cuts to ignite credit growth. Global headwinds, such as US tariff hikes and trade uncertainties, are weighing on business decisions. Domestically, some relief may come from the RBI’s phased 100-bps cut in the cash reserve ratio to be implemented by banks in four tranches. This should support bank credit, along with the expected GST reforms in September and festival season demand in October and November. The forecast of an above-normal monsoon could further support rural spending.

Even if corporates remain cautious, retail credit can continue to be the driver of credit growth as interest-sensitive segments like housing and autos expand along with personal loans. Yet, export headwinds may continue to sap business confidence. In hindsight, the RBI may have been prudent in aggressively easing monetary policy. Policy transmission lags mean that the front-loaded rate cuts may serve as much-needed life support for industry when growth pressures intensify later this year. Whether prescience or persistence defines this policy cycle remains to be seen.

*Views are personal