.png)

Yield Scribe is a bond trader with a macro lens and a habit of writing between trades. He follows cycles, rates, and the long arc of monetary intent.

November 2, 2025 at 3:13 PM IST

India’s bond yields eased on Friday after the Reserve Bank of India unexpectedly rejected all bids at its ₹110 billion auction of seven-year government securities, a move seen as a tactical defence of a key yield threshold. The benchmark yield retreated by about three to four basis points from Thursday’s close, though intraday trading showed the central bank’s determination to prevent a decisive break above the 6.60% mark for the ten-year, a level that had been repeatedly tested since late August.

Had the seven-year paper closed above that line, it would have marked a daily, weekly, and monthly finish above the crucial level for the first time since the Monetary Policy Committee meeting on October 1. The auction outcome averted that prospect, at least for now, and gave traders a reason to pause in an otherwise heavy-supplied market.

The Reserve Bank’s decision also avoided an inversion between seven- and ten-year yields.

If the gilt auction had cleared near the market’s 6.50% expectation, it would have exceeded the prevailing 10-year yield of 6.49%, creating an unpalatable signal for the issuer. Still, the relief is likely to prove temporary. Domestic bond markets continue to wrestle with weak institutional demand, an unstable foreign-exchange backdrop, and a shifting macroeconomic environment.

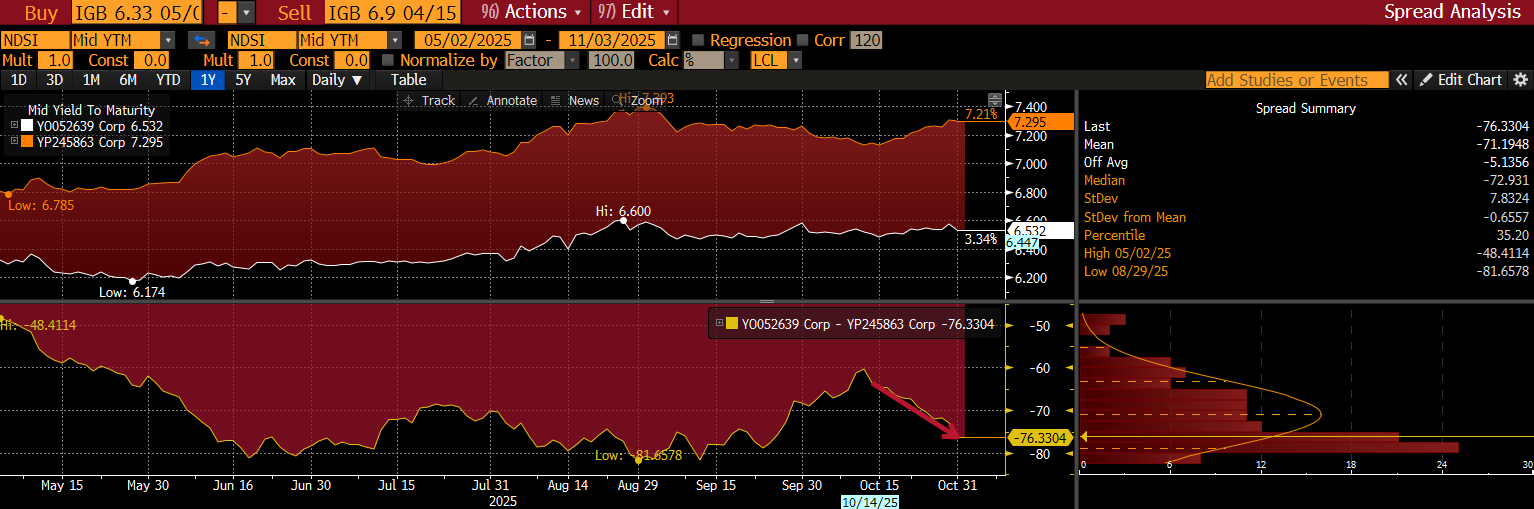

The announcement of the second-half borrowing calendar for 2025–26 had trimmed long-dated supply by roughly 5.5%, briefly flattening the yield curve. The spread between ten- and forty-year bonds narrowed to 62 basis points from August’s 78 basis-point high but has since widened again to about 76 basis points.

That is despite a lower-than-expected calendar for state development loans, pegged at ₹2.82 trillion for the October–December quarter against market estimates of ₹3.25 trillion–₹3.50 trillion. With actual state borrowings running at about two-thirds of the indicative schedule so far, the widening spread points to fragile demand at the long end even after reduced supply.

Pension funds have shifted more allocations towards equities following recent regulatory changes, while insurance inflows remain modest. As the financial year heads into its final quarter, state borrowing is expected to rise sharply again, which could push the long-end spread to new highs.

In the belly of the curve, demand has been equally tepid. Public-sector banks, already nursing mark-to-market losses on their trading portfolios, have shown limited appetite for fresh purchases in a volatile environment. Additions to the held-to-maturity book are minimal, given the restricted scope for reclassification later in the year, even if the central bank conducts open-market operations in early 2026. Rising credit demand has also reduced banks’ investment flexibility as lending growth tracks improving consumption.

Expectations of a policy-rate cut in December are fading. A formal India–United States trade deal is likely after the Bihar elections, while recent tax and goods-and-services-levy cuts are expected to lift consumer spending.

With second-quarter GDP growth projected near 7.2%, the central bank would need to see clear signs of softening growth to justify easing. Recent public comments from the MPC members suggest confidence in domestic momentum, implying that their inflation outlook remains forward-looking but their growth reading is still backwards-leaning.

Global cues are not helpful either.

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s remark that a December rate cut is “not a done deal” has left little room for monetary accommodation in emerging markets. The rupee has already absorbed the impact of nearly $20 billion in central-bank intervention between mid-September and end-October, only to end up close to where it started. The RBI’s forward book is estimated at $70 billion as of October end, indicating that any rupee gains linked to a trade deal could be fleeting as the dollar index strengthens globally.

Liquidity conditions remain comfortable, and core liquidity is estimated at around ₹3.25 trillion, with the overall system broadly balanced. Two tranches of the 25-basis-point CRR unwind this month and will inject roughly ₹1.25 trillion, removing the need for immediate open-market purchases. Any durable liquidity operations are likely to be deferred until the December policy review.

For now, the market’s bias is to sell on rallies. The only catalyst capable of altering sentiment decisively might be the inclusion of Indian government bonds in the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Index, a move not expected before January 2026.

Temporary reprieves, such as Friday’s post-auction bounce, may punctuate the trend, but these are typical of bear market rallies that climb briefly before a deeper capitulation.

The fundamental mismatch between supply and demand remains. Expanding state-level welfare spending has created a glut of long-duration paper with few natural buyers. Until that imbalance is corrected, India’s local bond yields will stay under pressure, regardless of the central bank’s tactical defences.