.png)

February 15, 2025 at 9:30 AM IST

Alok, a professor, and Pavan, a research associate, are affiliated with the School of Economics at the University of Hyderabad

Urban India has much to cheer about from the Budget for 2025-2026. The proposed tax relief is expected to have a multiplier effect through increased disposable income and leave more room for savings for the country’s middle class. However, there’s much the budget also misses out on. In her eighth consecutive budget presentation, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman stated that urban development was a key domain, but the numbers point to a different story. Let’s examine how recent budgets have addressed urbanisation and whether this approach can tackle urban India's challenges.

The 2011 Census estimated that about 31% of India was urban. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, quoting published studies and NITI Aayog’s research, stated that over the last decade, there has been a significant rise, albeit at a slow pace, in urbanisation. This, however, is yet to be reflected in actual numbers till the next Census is conducted. The figure is expected to be more than 40% by 2030.

The debate over the extent of urbanisation aside, it is undeniable that there has been a rise in the number of urban areas. In its World Urbanisation Prospects (Revised) Report in 2022, the United Nations Development Programme noted India would add 416 million more urban dwellers by 2050 while adding two more 5-million-plus cities and taking the figure to seven from the current number five by the same period. Similarly, it is estimated that we would have 10 more cities with a population of 1-5 million. A NITI Aayog report from 2022 estimated that urban areas in India contributed close to 60% of GDP. Therefore, the importance of urban agglomerations is only expected to increase in the coming years owing to their capacity to generate economies of scale and scope, bring together different domains and sectors and help create value addition.

Urbanisation is projected to reach 50% by 2050, barring scepticism. It is recognised that there is a need to allocate a massive level of investment for providing improved facilities as well as upgrading existing service delivery mechanisms and physical infrastructure such as roads and mass rapid transit corridors involving metro rail, suburban rail and bus transport systems, which are extremely capital intensive.

A high-powered committee set up by the then Ministry of Urban Development in 2011 estimated that ₹39.2 trillion (at 2009-10 prices) was necessary to build urban infrastructure over a 20-year period. This translates to a whopping ₹2 trillion annually. This amounts to about 1.1% of GDP for urban infrastructure development. (In 2021-2022, spending stood at 2.8% of GDP)

Status Quo

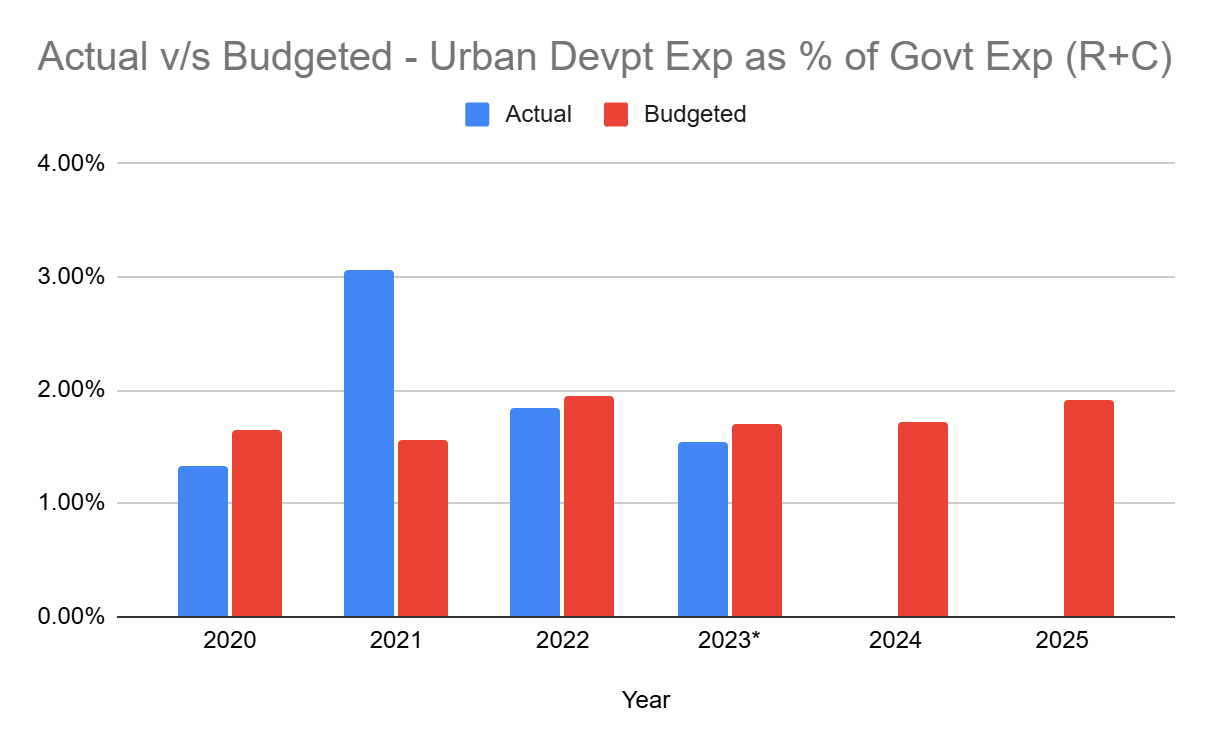

In recent years, including the Budget for 2025-2026, there has been a mention of impetus to urbanisation. Annual allocations for the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs as a share of total government spending have fluctuated. If we consider the expenditure on urban development as a percentage of the total expenditure outlay of the government since the pandemic, it is less than 2%.

The ministry’s actual expenditure has fallen short of budgeted allocations for its operations and programmes for three years (2020, 2022, 2023) except for 2021, when the actual expenditure, as a proportion of total government outlay, exceeded 150 basis points from its budgeted amount. This was recorded despite a marginal increase in the actual expenditure by MoHUA in 2022 (compared to the Budget Estimate).

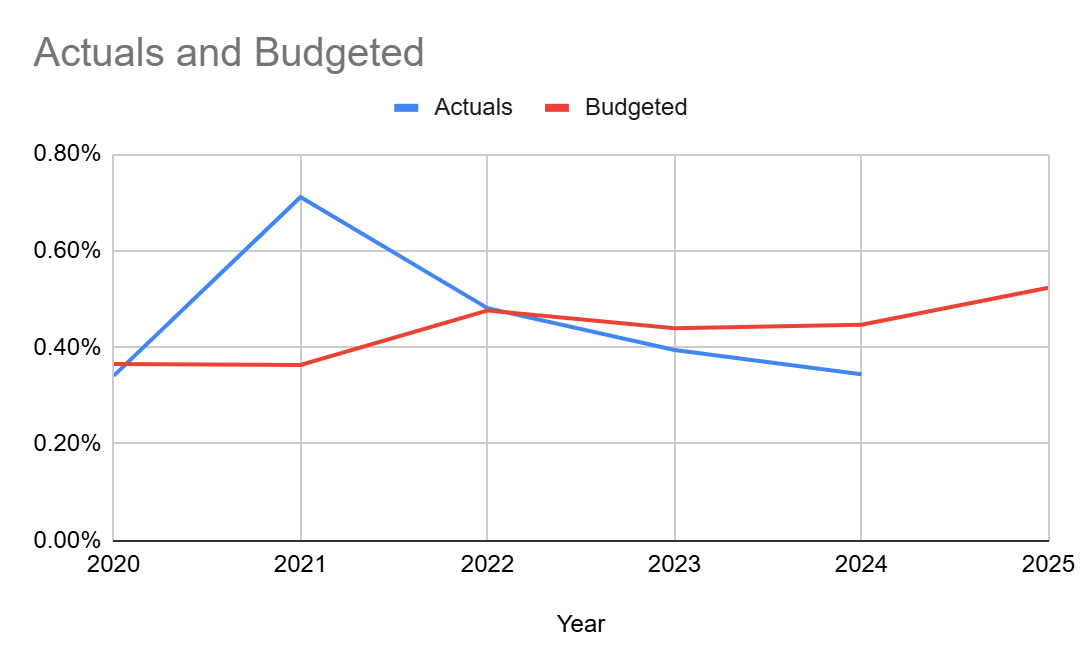

As a proportion of India’s GDP at constant prices, these outlays remain well below the committee’s projections.

It is to be noted that while there has been a noticeable rise from 0.3 % of GDP in 2020-2021 to 0.5% in 2025-2026, the outlays are still much less than what is required. The committee’s recommendations were, as a matter of fact, made during the days of the now-defunct Planning Commission.

Notably, schemes such as Swarna Jayanti Shehari Rozgar Yojana, Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, and Basic Services to Urban Poor were withdrawn and replaced with Central Sector Schemes like Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation – AMRUT - Smart Cities Mission and Deendayal Anna Yojana - National Urban Livelihoods Mission.

Fund Use

AMRUT focuses on fixing urban sanitation, water and provision of similar amenities in urban areas. Meanwhile, the Smart Cities Mission aimed to upgrade cities with technological support and area-based development.

It included retrofitting 100 cities, improving the data systems, and supporting technical interventions such as Integrated Traffic Management Systems to resolve congestion, improve e-governance and aid in real-time security.

As of date, about 93% of the work appears to have been completed, with about ₹1.5 trillion being spent on 7,482 projects in all 100 smart cities. Of these, 20% of the projects pertained to smart mobility, followed by about 20% related to social and economic infrastructure. About 18.5% were related to water and sanitation hygiene, while projects related to the environment were only 1.8%. Only 5% of completed projects followed the public-private partnership model, while 48 % were funded through the Mission, highlighting the many funding challenges.

On the other hand, data from the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation shows that the total outlay is about ₹2.9 trillion for five years (about ₹590 billion each year), with central assistance of ₹767.60 billion.

However, the budget documents show less utilisation than the earmarked amount, which also varied significantly. This trend is observed in other schemes as well.

The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana - Urban, which was given huge allocations during 2021-2022, saw a marked decline, with only half of its actual allocation being made in the subsequent years while less utilisation persisted, except for 2022. Its budget allocation rose sharply between 2020-2021 and 2024-2025. However, in this year’s budget, there has been a 38% cut from the previous budget estimate in the allocation made for the scheme.

The Smart Cities Mission will end on Mar 31, 2025., raising questions about how the continuity of the projects built during the scheme period can be maintained. It is necessary now to increase the planning capacity for urban local bodies and enhance the funding for local governments in the aftermath of the Smart Cities Mission to build on what is learned from it.

On the other hand, relatively efficient use of funds has been observed in metro projects (excluding NCR Transport Corporation funding), which is the second major head for MoHUA after PMAY-U. The actual spending went up by 171% between 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 and has increased over the years, pointing to enhanced central assistance for various metro rail projects in the country, with this year’s budget setting aside about ₹312.39 billion.

Additionally, ₹13.10 billion has been set aside for the PM e-Bus SEWA scheme for cities to seek central assistance purchasing electric buses. This year’s budget also saw the introduction of an ‘Urban Challenge Fund’ with allocation of ₹100 billion with a planned corpus of ₹1 trillion to fund up to 25% of bankable urban infrastructure projects with additional allocations being made for enhancing social security of urban poor and street vendors, which are welcome.

These micro-fixes are long due to the boom of the gig economy and the lack of adequate social protection for gig workers. However, there are also broader issues that the budget should have ideally addressed.

More Room

While increasing funding for specific projects, the amount has been reduced substantially for schemes like PMAY-U. The increased outlay for urban development is hoped to be followed up with efficient use of allocated resources for maximum outcomes.

There is much more room for the budget to actually address the growing challenges of urbanisation. As the rural-to-urban migration rate in the country touches 19%, it is pertinent to note that almost 30% of the urban settlements live in slum areas with inadequate sanitation, lack of hygiene and limited public transport options. This necessitates that going forward, focus on the urban poor through assessments - Urban Poor Quality of Living Surveys - and earmarking money for the urban local bodies to directly tap in be undertaken.

As cities still suffer from problems of inadequate autonomy vis-a-vis funding and limited financing options, plans for scaling up transit networks, re-designing cities and planning capacity enhancement are in limbo.

There is an urgent need to reform city governance and increase urban infrastructure funding to at least 1% of the GDP, with a significant share coming through budgetary support along with other financing mechanisms such as public-private partnerships and loans. This step,as envisaged by the high-powered committee, will ensure urban India is prepared to achieve the social development goal of sustainable cities and communities by 2030 and also plan ahead to ensure existing cities as well as the upcoming cities become ‘growth hubs’ while also being inclusive and sustainable in the long-run.

1.Revised Estimates (RE) for MoHUA’s outlay has been considered for 2024 while rest of the figures are Actuals.