.png)

God Laughs, Markets Listen, and the Reddyisms that Still Resonate

From wit and ambiguity to humility and integrity, YV Reddy’s new book shows why values matter more than plans in an uncertain world.

Kalyan Ram, a financial journalist, co-founded Cogencis and now leads BasisPoint Insight.

August 31, 2025 at 4:45 AM IST

In July 2008, I wrote a piece in NewsWire18 (later called Cogencis) on the language of Yaga Venugopal Reddy, then Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. I called it a study in “Reddyisms”—phrases that both baffled and delighted.

He would speak of “sensitivising markets” or describe the “trilemma” of policy trade-offs in ways that were not in any textbook but soon entered the financial lexicon. The piece drew an unusual response: Reddy himself, in his neat hand, scribbled on the printout’s margins “very likeable piece, entire piece very readable” and arranged to send it to me. From a man whose entire career was built on carefully weighed words and constructive ambiguity, that short line of appreciation has stayed with me as a prized possession.

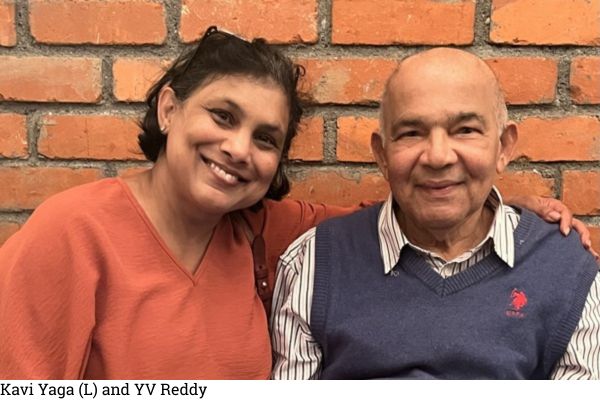

What struck me then was how language became policy. A central banker who could describe the exchange rate as a battle between God and the Devil was not merely being theatrical; he was framing uncertainty in ways that both educated and disarmed. Yet reading the chapter “God Laughs and Other Reflections”, co-authored with Kavi Yaga in the book Work Wisdom Legacy – 31 Essays From India, compiled by Reddy, one realises that the wordplay was only the visible surface. Beneath it lay a philosophy of humility, integrity, and humour that guided his professional life as well as his personal conduct.

This column explores those reflections, placing them in today’s economic and policy context, before returning to that scribbled note of 2008 which, in its modest way, anticipated the voice of this book.

***

Wit as a Policy Instrument

Among the book’s most charming essays is his defence of humour in public life. “Humour is everyone’s best friend,” he writes, insisting that wit need not undercut seriousness. Indeed, as his career shows, humour was often his sharpest instrument of policy. The ability to cloak an admonition in a quip or to dissolve tension in a press conference with a parable did not dilute the Reserve Bank’s credibility; it strengthened it.

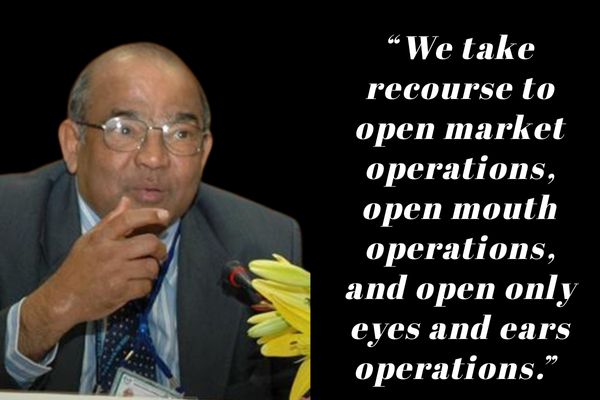

The most famous example remains his comment at the Bank for International Settlements in Lucerne in 2008, where he classified RBI’s tools in the defence of financial stability: “We take recourse to open market operations, open mouth operations, and open only eyes and ears operations.” The room of central bankers may have laughed, but the point was clear: markets could be managed as much by words as by balance-sheet moves, and sometimes by restraint. Humour became a form of signalling, a way of saying something without over-committing, and a means of keeping options open.

In his essay in the book, Reddy notes that ambiguity is not a flaw but a discipline.

By remaining deliberately non-specific, he gave himself space to adapt. Markets may have called it opacity; he saw it as honesty in the face of uncertainty. The lesson for today’s policymakers is uncomfortable: in an age of social media, leaders often feel compelled to provide instant clarity. Yet clarity can turn into rigidity, and rigidity is dangerous when shocks—from tariffs to pandemics to wars—arrive unannounced. Perhaps Reddy’s humour and ambiguity were not evasions but shields, protecting institutions from being boxed in.

I once asked him what he thought of Thailand’s Tobin tax–style experiment to curb capital flows. I had framed it cleverly, I thought. I had actually asked if he liked what Thailand did, as India too was facing similar challenges. True to form, he would not be drawn into a direct comment. Instead, with a half-smile, he offered a line that said everything and nothing at once: “What’s there not to like about Thailand?”

***

The ‘Three I’s’ Pass Muster

If humour softened edges, integrity formed the bedrock. One of the most resonant sections in the book sets out his “three I’s” test: Integrity, Intellect, Industry. These were his criteria to assess colleagues, and by implication, to assess himself. Each word was chosen with care. Integrity was non-negotiable, the anchor of credibility. Intellect was not raw cleverness but the capacity to contextualise, to see India’s economic realities without being overawed by imported theory. Industry was diligence, the ability to master detail and persevere.

A tribute from a Nobel laureate contextualises the point. Post the Lehman crisis, Joseph Stiglitz said in 2009 that the US economy would not have been in such a mess had Reddy been the nation’s central bank governor.

Reddy did not have it easy. He endured flak for keeping interest rates high, prudential norms tight, and going after capital inflows that didn’t come through the clearest of routes. Reddy was indeed credited with protecting India’s economic and financial stability. His autobiography, Advice and Dissent, is quite instructive.

Applied to today, the three I’s read like a quiet rebuke to our times. Policy institutions now operate under intense political scrutiny and global market pressure. Integrity is tested not only by lobbying and politics but also by the temptations of celebrity. Intellect risks being reduced to quick takes and social media soundbites. Industry is endangered by the rush to outsource analysis to models or algorithms. In holding up his triad, Reddy is telling a new generation of policymakers that credibility rests not on charisma or clever communication. but on these old-fashioned virtues.

The Reserve Bank, to its credit, continues to enjoy respect largely because successive leaders have lived by versions of this standard. But whether other institutions in India’s political economy still measure up is a harder question.

Reading Reddy today is a reminder that credibility is not declared; it is earned, slowly, through conduct and consistency.

***

‘Haddu-Paddu’

In another memorable essay, Reddy uses a Telugu phrase—haddu-paddu, meaning limits—to argue that governance is as much about recognising boundaries, as about pushing frontiers. Linked to this is his advice: assess, don’t judge. The subtlety matters. Assessment is contextual, provisional, open to change; judgement is rigid and often final. For a central banker, the difference could mean flexibility in liquidity management or fiscal rules, as opposed to being trapped by rigid targets.

The relevance today is obvious. India debates whether fiscal deficit targets should be fixed in stone or adjusted to growth cycles. The Reserve Bank reviews its liquidity framework and the role of the Standing Deposit Facility. Globally, the pandemic forced central banks to abandon long-cherished rules, flooding markets with liquidity and tolerating debt levels that once seemed unthinkable. In all these, discretion—knowing when to bend and when to hold—was vital.

Reddy’s reflections remind us that not all limits are numerical. Some are contextual, cultural, and even moral. A policymaker who mistakes a number for an absolute can do harm. The lesson is humility: to recognise limits not only in others but in one’s own understanding. In a world that worships metrics, that is a deeply counter-cultural insight.

He once added another Telugu phrase to the same theme: samayam sandharbham mukhyam or time and context are so important. For Reddy, this was not a cliché but a principle of policy. A measure that was wise in one season could be reckless in another; a stance that reassured in calm could destabilise in crisis. This sensitivity to timing and circumstance distinguished his approach. Limits were not static fences; they shifted with context, moving with time and circumstance. Policy, in his telling, was less about timeless rules than about the wisdom to read the moment.

***

The Art of One Extra Option

Perhaps the most pragmatic lesson in the book is his maxim: always keep “one extra option at no extra cost”. This was not a trick, but a philosophy. Whether negotiating at the World Bank, discussing reforms in Delhi, or steering liquidity in Mumbai, Reddy sought to avoid being cornered. The additional option gave room for manoeuvre, a psychological edge, and often the space to build consensus.

In today’s context, this wisdom applies as much to diplomacy as to economics. India negotiates trade frictions with the United States and juggles free-trade agreements with partners from the Gulf to East Asia to Europe. Having an extra option—another market, another instrument, another alliance—reduces vulnerability. In monetary policy, too, keeping one instrument in reserve can deter speculation or calm markets.

Reddy’s pragmatism was never cynicism. He did not argue for duplicity but for resilience. The moral is clear: rigidity may look principled, but it often leaves policymakers exposed. Flexibility, if grounded in integrity, is not weakness but strength. In an uncertain world, optionality is survival.

***

Theory vs Commonsense

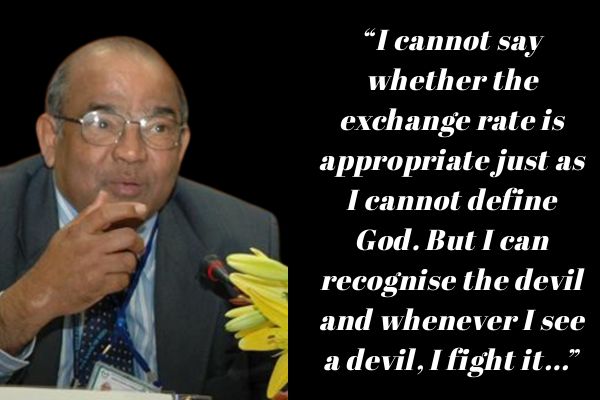

Reddy’s scepticism of theory for its own sake is another theme that shines through the book. He often warned that imported economic models could not capture the messiness of Indian realities. His remarks on the foreign exchange market captured this vividly: “I cannot say whether the exchange rate is appropriate just as I cannot define God. But I can recognise the devil and whenever I see a devil, I fight it. Nor can I say what a devil looks like because it comes in different forms, different types, and different density. That’s exactly how the forex markets are.”

Although unconventional at times, such comments were effective.

After Reddy’s “God-devil–foreign exchange” articulation, the government moved to place curbs on participatory notes and on overseas borrowings by Indian companies, as surging inflows were putting upward pressure on the rupee and squeezing exports. It was almost a case of the impossible trinity: the RBI could not simultaneously maintain a stable exchange rate, an open capital account, and monetary policy autonomy. By framing the problem in parable-like terms, he made both the dilemma and the rationale for action intelligible.

This tension between theory and commonsense is sharper today. Policymakers rely heavily on armies of data scientists, algorithms, and artificial intelligence tools, promising precision. Yet the shocks that dominate—pandemics, tariffs, climate events, financial tremors—are exactly those that models fail to anticipate. The danger is to mistake forecasts for fate, outsourcing judgement to formulas.

Reddy’s insistence on commonsense was not anti-intellectual. It was a call to temper theory with context, to see models as tools rather than masters. His metaphors were not evasions but clarifiers, making complexity accessible without stripping it of nuance.

In a country of structural contradictions and volatile shocks, commonsense is not a second-best to theory; it is the only safeguard against being precisely wrong.

***

Personal Conduct Bringeth Institutional Credibility

Perhaps the most revealing parts of the book are not about policy at all, but about personal choices. Reddy describes carrying his own food while on official tours to avoid even the perception of favours. He recalls telling himself, “It is not my job to be liked.” He believed that credibility of an institution flows from the conduct of individuals, especially those at the top.

In an era where transparency is instant and lapses are amplified, these lessons are even more relevant. A careless remark, an imprudent gift, a moment of vanity can erode years of institutional trust. Reddy’s spartan discipline gave the Reserve Bank a moral authority that statistics alone could not supply. It is no coincidence that during his tenure, despite market volatility, the RBI retained credibility as the anchor of stability.

Personal restraint is not fashionable today. Leaders are expected to be visible, engaging, and even entertaining. But institutions built on spectacle are fragile. Reddy’s example is a reminder that often the most powerful signal is silence, and the most enduring credibility is restraint.

***

Independence, Accountability, and Identity

The book revisits the perennial question of central bank independence. Reddy’s formulation was characteristically nuanced: the RBI was “independent within government”. De jure, it reported to the Finance Ministry; de facto, it carved autonomy through credibility, professionalism, and communication.

His 2008 speech in Lucerne elaborated this: accountability to Parliament was mediated through the Ministry, and communication was constrained by political economy realities. Yet, by being transparent and by explaining its reasoning, the RBI enhanced its independence in practice.

This conception is strikingly relevant today. Across the world, central banks are under pressure—accused of being too close to markets, too distant from citizens, or too submissive to governments. In India, debates rage about fiscal dominance, monetary-fiscal coordination, and the space for rate cuts amid political imperatives. Reddy’s framework—that independence is relational, earned by conduct, not granted by statute—remains one of the most honest answers.

Independence, he suggests, is not a fortress but a negotiation. The RBI is not an island; it is a part of the government, but with its own compass. This nuanced balance is worth recalling when institutions are tempted either to flaunt autonomy or to surrender it.

***

God Laughs — Humility as the Final Lesson

The book closes with a disarming reflection: God laughed at all his plans.

Reddy wanted to be an academic, then found himself in the IAS, then in finance, and finally as RBI Governor and Finance Commission Chairman. None of it, he says, was foreseen. Plans mattered less than adaptability; control was often an illusion.

For policymakers, this is the deepest lesson. The world is full of shocks no model predicts—pandemics, wars, financial crises, tariffs, and climate disruptions. The arrogance of control is always punished. Humility, humour, and adaptability are the constant guides.

This humility is not fatalism. It is not a call to abandon planning, but to temper it with perspective. God may laugh at human plans, but policymakers who can laugh at themselves, who can acknowledge their limits and change course are more likely to serve their societies well.

In 2007, when Reddy scribbled “very likeable piece” on my article about his wordplay, I read it as a personal kindness. Today, reading the chapter “God Laughs and Other Reflections,” I see it differently. His language was not just a trick; it was a window into a philosophy. Ambiguity was humility. Humour was a discipline. Integrity was armour.

The book with Kavi Yaga distils that philosophy—less in the language of a central banker than in the tone of a reflective teacher. It shows that behind every Reddyism was a readiness to admit uncertainty, a willingness to trust values over vanity, and a belief that plans are provisional.

As I close this essay, I return to that touchstone. God may laugh, but Reddy’s words continue to speak. They remind policymakers that credibility is born of humility, humour, and humanity. And they remind those of us who write about them that sometimes, the most powerful sentences are the ones that refuse to say everything.