.png)

Budget Must Treat Critical Minerals as Economic and Security Assets

India’s growth and security now depend on critical minerals. This Budget must move past intent and set out how the country plans to secure supply.

Chandrashekhar is an economist, journalist and policy commentator renowned for his expertise in agriculture, commodity markets and economic policy.

January 23, 2026 at 5:01 AM IST

India’s growth ambitions and its security concerns are converging on the same constraint: access to critical minerals. What once looked like a distant supply issue has moved to the centre of the energy transition, manufacturing strategy and defence planning. Without dependable access, both growth and strategic autonomy begin to look fragile.

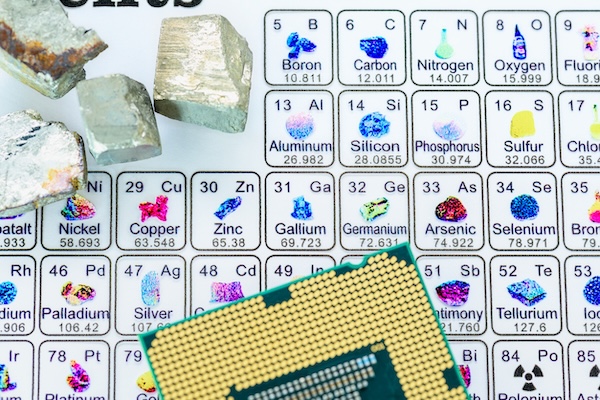

These minerals sit inside electric vehicles, solar panels and wind turbines. They are just as critical to electronics, defence equipment, healthcare devices and space technologies. Lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, copper, gallium, germanium and indium may sound technical, but they have quietly become strategic commodities rather than industrial inputs.

India’s dependence on imports for many of these minerals is therefore a growing weakness. The world has become a rougher place to operate in. Over this decade, geopolitics has intruded into trade, economic rivalry has hardened and the old assumptions about smooth, reliable supply chains have quietly collapsed. There is no obvious path back to that earlier order.

Sanctions, trade controls, protectionism, resource nationalism and stockpiling are no longer exceptions; they are standard policy tools. Supply chains break more easily, access is less assured and prices swing without warning. For an economy trying to scale up manufacturing while safeguarding its strategic interests, this is no longer a peripheral risk. It belongs at the heart of policy.

That is why India needs a clear, long-term strategy for critical minerals and rare earths. The National Critical Minerals Mission, launched in January 2025, is a necessary starting point. By taking in the full value chain, from exploration and mining to processing and recovery, it recognises the scale of the task. The real test, however, will be whether this intent is sustained through consistent policy and execution.

Securing critical minerals cannot be a siloed policy exercise; it must become a national effort — indeed, a national obsession — requiring close coordination between the Centre and the States.

Strategic Focus

The amended Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act lists 24 critical minerals under Part-D of its First Schedule, including lithium, nickel, tungsten, titanium and graphite. These minerals are designated critical because production and supply are concentrated in a few geographies globally. They are also far more difficult to explore and mine than bulk or surfacial minerals.

India does have reserves and resources of some critical minerals, but they will not unlock themselves. What is needed is faster and more systematic exploration, pursued on several fronts at once. Domestic exploration has to be stepped up through transparent processes. The private sector has to be part of this, but without mining rights ending up cornered by a few players. Overseas partnerships and foreign capital can fill gaps in money and technology. Recycling and recovery from waste also need to be treated as real supply options, with tough pollution safeguards in place. Strategic reserves, finally, are no longer optional but essential.

International partnerships, in particular, need careful design. Inviting countries such as the US to invest in exploration and mining can bring capital and technology, but safeguards must ensure India’s assured share of output and long-term supply security.

The upcoming Union budget 2026–27 must therefore do more than acknowledge the sector. It must lay out a clear roadmap with measurable milestones. That, in turn, requires a prior and realistic assessment of India’s mineral requirements over the next 5, 10 and 20 years.

Mining is inherently a long-gestation, energy-intensive activity. Years often pass between initial investment and commercial output. Mining is a long game. Capital will come only if policy stays steady. The Finance Minister cannot afford to push this decision further down the road.

Critical minerals are no longer just inputs for industry. They are economic assets and strategic shields. The Budget must recognise them as such.

Also Read: Critical Minerals for Steel Tariffs, India Should Play its Cards Well