.png)

Amitabh Tiwari, formerly a corporate and investment banker, now follows his passion for politics and elections, startups and education. He is Founding Partner at VoteVibe.

October 14, 2025 at 10:49 AM IST

In the heartland of Indian politics, Bihar stands at a pivotal moment as an age-old question returns with renewed urgency: can the state finally move beyond its deeply entrenched caste politics? With a crucial election on the horizon, the answer, for now, seems to be not yet. As the saying goes, in Bihar, people don’t just cast their votes, they cast their caste.

The numbers tell a story of caste loyalty so profound that it shapes not just voting patterns but also very architecture of political representation in the state.

The Iron Grip of Caste Identity

This preference isn't merely a voting pattern; it's a lived reality that permeates every aspect of Bihar's political ecosystem, from ticket distribution to coalition arithmetic.

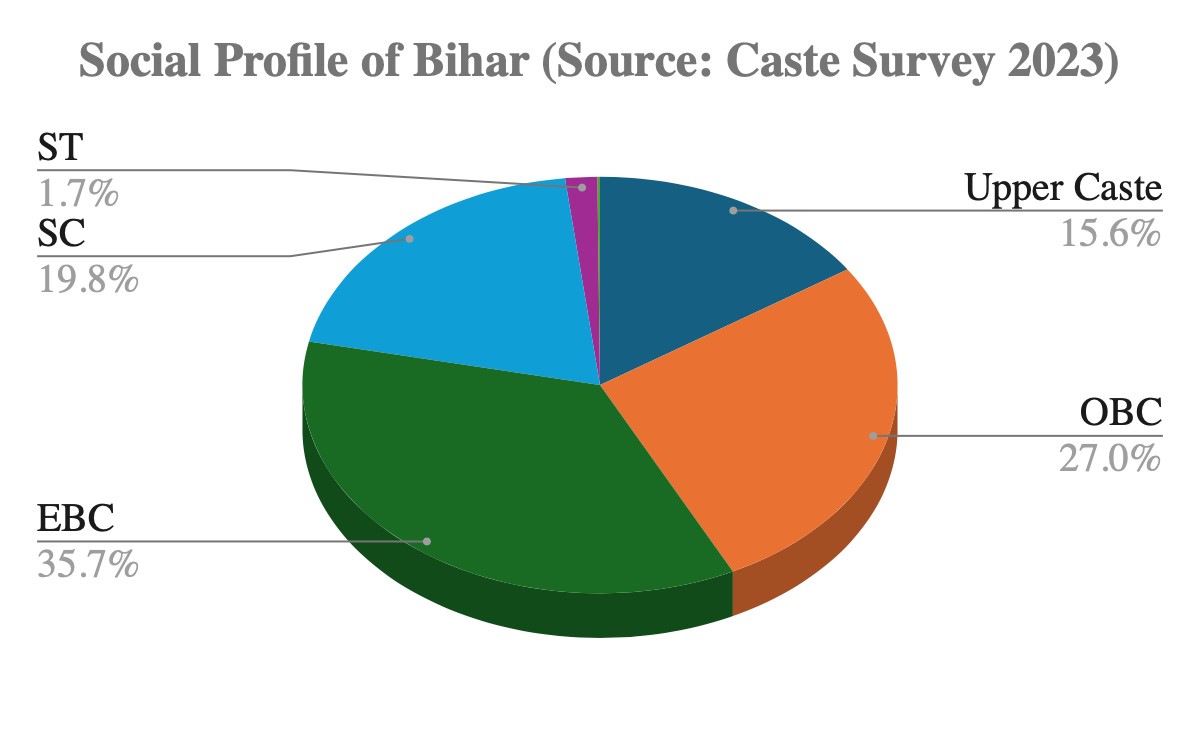

The state's demographic composition reflects India's complex caste mosaic. Hindu Upper Castes constitute 11% of the population, while Yadavs account for 14%, and Non-Yadav Other Backward Classes represent 11%. The Hindu Extremely Backward Classes form the largest group at 26%, Muslims comprise 18%, and Scheduled Castes make up 20%.

This demographic diversity, however, hasn't translated into proportional political representation or power-sharing.

The Great Divide: NDA vs MGB

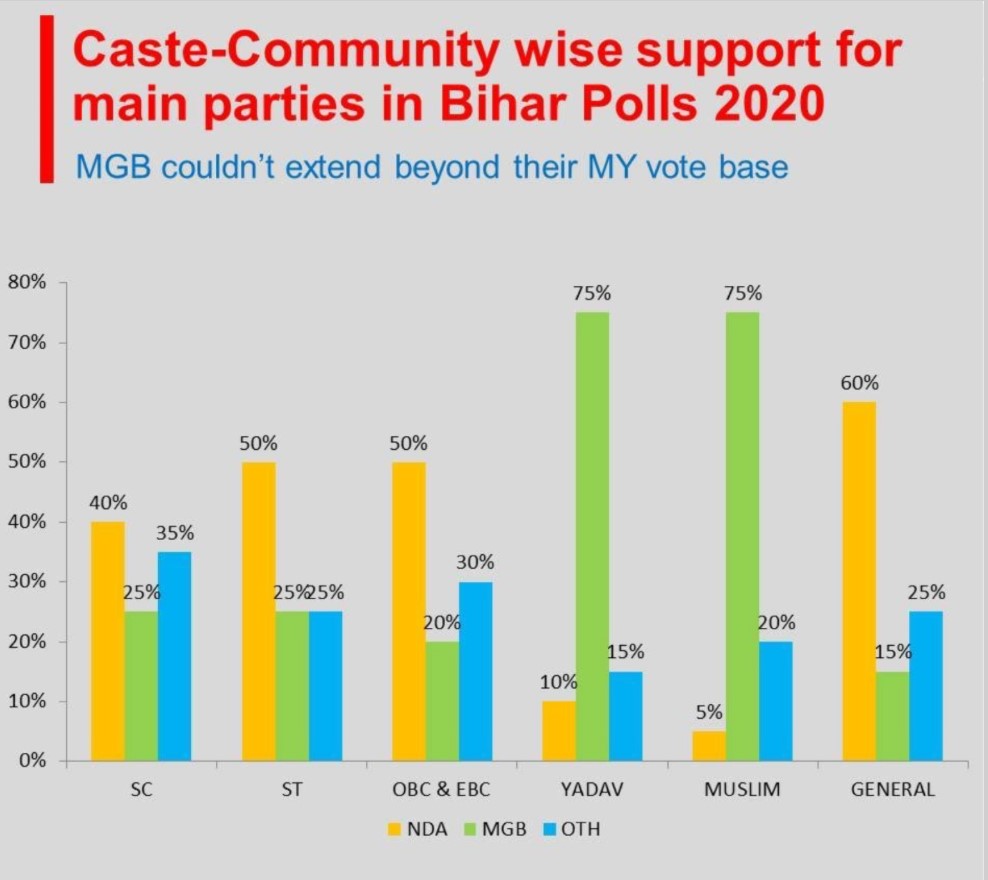

In contrast, the Mahagathbandhan draws its strength primarily from the Yadav and Muslim communities, a coalition often referred to as the Muslim-Yadav combine, accounting for 32% of population. The MY support for MGB has shown remarkable consistency and growth.

According to surveys, in the 2020 assembly elections, 75% of this combine backed the MGB. This figure surged to over 80% during the 2024 Lok Sabha polls, demonstrating the deepening consolidation. This bloc voting represents both the MGB's greatest strength and its most significant limitation as it gives a headstart with 24-25% vote share but at the same time fuels polarisations.

On the other side, the NDA's caste coalition appears more diverse but perhaps less intense in its loyalty with higher leakages. Over 60% of upper caste voters support the NDA, while 50% of Non-Yadav Other Backward Classes/EBC and ST, 40% of SC voters back the alliance. The relatively lower support among these groups compared to MY consolidation suggest there's more fluidity and room for political manoeuvring among these communities.

That’s why MGB with 32% core vote recorded 37% vote share in 2020, and NDA with 68% core vote recorded 43%. MGB received around 25% support from anchor voting segments of NDA and this needs to be increased to at least 33% for a chance at making the next government. That’s why MGB is wooing EBC and SCs through key promises, inducing them to switch loyalties.

The 2024 Shift: Constitution Narrative Changes SC Dynamics

MGB gained 35% votes among Dusadh/Paswan community and 28% among other SCs at the expense of NDA which lost 19% and 18%, respectively. This breakthrough demonstrates that caste loyalties, while formidable, aren't entirely unwavering when issues of fundamental rights and representation are at stake.

For the MGB to expand beyond its MY base, making substantial gains among EBC and SC voters remains imperative. The challenge is formidable, these communities have developed their own political consciousness and aren't merely waiting to be absorbed into larger coalitions.

The Congress, part of the MGB, is trying to woo the EBCs through the “Nyay Sankalp Patra”, promising new laws similar to SC-ST Prevention of Atrocities Act. It is also wooing the SCs by appointing Rajesh Ram as its state president.

The Persistence of Caste Dynasties in Constituencies

|

SAME CASTE / COMMUNITY WINNING (2010, 2015, 2020) |

SAME CASTE / COMMUNITY WINNING SEAT (2010, 2015, 2020) |

||

|

Group |

No. of Seats |

Group |

No. of Seats |

|

Yadav – OBC |

27 |

Yadav – OBC |

18 |

|

Rajput – UC |

13 |

Rajput – UC |

15 |

|

Muslim |

9 |

Muslim |

9 |

|

Koeri – NYOBC |

9 |

Koeri – NYOBC |

7 |

|

Bhumihar – UC |

8 |

Bhumihar – UC |

13 |

Source: Author’s Calculations

This means that nearly 90% of Bihar's assembly constituencies show strong caste-based voting patterns that transcend party affiliations. More strikingly, just five groups, Yadavs, Muslims, Koeris, Rajputs, and Bhumihars, account for 60% of all MLAs (143/243 in 2020) and dominate the state's political landscape.

The irony is sharp: these five groups represent merely 42% of Bihar's population, revealing a significant representation gap. Also, even the NDA has25%of all Yadav MLAs which is considered as MGB core vote bloc, while MGB has 33% of all Rajput+Bhumihar+Koeri MLAs, a core NDA core vote bloc, highlighting their dominance across parties..

The Representation Deficit

This underrepresentation creates both political grievance and opportunity, fertile ground for parties seeking to expand their support base. It also explains why parties are increasingly focused on EBC outreach, recognising this community's demographic heft and political potential.

|

5 Caste / Community Groups Dominate Bihar Politics |

|||

|

Caste/Community |

No. of MLAs 2015 |

No. of MLAs 2020 |

2/3 & 3/3 Wins in |

|

Yadav |

61 |

52 |

45 |

|

Muslim |

24 |

19 |

18 |

|

Koeri |

20 |

16 |

16 |

|

Rajput |

20 |

28 |

28 |

|

Bhumihar |

18 |

21 |

21 |

|

Total |

143 |

136 |

128 |

|

% of Assembly |

58.8% |

56.0% |

52.7% |

|

Source: Author's Calculations |

|||

That’s why parties like AIMIM received good support from Muslims in Seemanchal where it bagged five seats damaging MGB prospects. It's all about representation in Bihar. Voters cast their caste as they believe community candidates would work for championing their rights.

Political responses to Bihar's caste calculus reveal how even development-focused leaders must acknowledge ground realities. Prashant Kishor, who built his reputation on data-driven, development-oriented politics, is now carefully balancing caste considerations in ticket distribution. His strategy appears two-pronged: targeting EBCs to weaken the Janata Dal (United) and courting Muslims to undermine the Rashtriya Janata Dal giving them 27% and 18% tickets in its two lists.

Beyond Caste: A Distant Horizon?

The question of whether Bihar will move beyond caste politics cannot be answered with simple optimism or pessimism. The data suggests that caste remains the primary lens through which voters view politics, parties distribute tickets, and coalitions are formed.

Yet, the underrepresentation of EBCs and Muslims, the marginal gains made through issue-based campaigns, and the increasing sophistication of political strategies hint at potential shifts. The real inflexion point may come not when Bihar moves beyond caste, but when its politics more accurately reflects its demographic diversity, giving voice and representation to communities currently on the margins of power.

Until then, caste remains not just a factor in Bihar's politics—it is Bihar's politics.