.png)

Are Indian Cities Finally Being Taken Seriously?

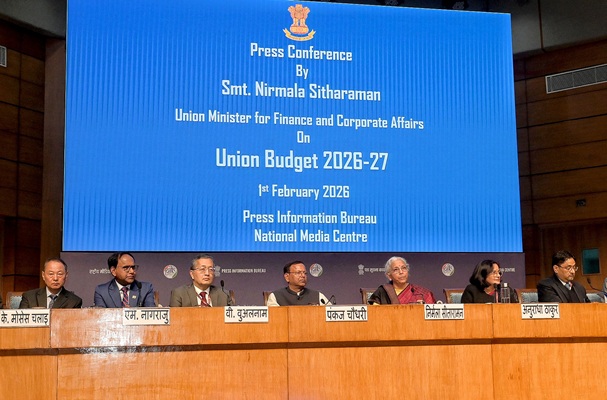

The Budget signals a shift in urban policy, focusing on fiscal transfers, metro-scale planning, and stronger municipal capacity over headline-grabbing schemes.

Shilpashree Venkatesh is a research professional with expertise in macroeconomics, real estate, and infrastructure, focused on growth trends.

February 12, 2026 at 8:32 AM IST

The urban-focused announcements in the Union Budget 2026 offer renewed hope for equitable and sustainable growth in India’s cities. Urban areas are estimated to contribute nearly 65% of the country's GDP while housing around 40% of the population. Major metropolitan regions such as Delhi NCR, Mumbai, and Bengaluru are deeply integrated into global economic networks and function as critical engines of growth.

Projections suggest that India’s urban population could exceed 600 million by 2030, with a substantial share of new job creation concentrated in urban and peri-urban regions. This trajectory underscores the need for sustained, well-governed urban development anchored in strategic investment and institutional reform.

Policy attention to cities is not new. For decades after Independence, development strategy was largely shaped by food security imperatives and the political economy of agriculture, leading to relative neglect of urban planning and infrastructure. From the mid-2000s, however, urban development began receiving more systematic policy attention.

The Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, launched in 2005, marked the first major attempt to link urban infrastructure with governance reform. The mission covered 63 cities identified broadly based on the 2001 Census. Between 2005 and 2014, JNNURM mobilised investments exceeding ₹1.3 trillion across urban transport, water supply, sewerage, and housing. It also sought to catalyse reforms, including the adoption of double-entry accounting systems and improvements in property tax administration.

However, implementation weaknesses were evident. Audit findings pointed to delays in project completion, deficiencies in project preparation, and weak operations and maintenance frameworks. In its early years, completion rates lagged expectations, highlighting the challenge of translating central allocations into durable urban assets. The experience revealed a recurring gap between policy ambition and local execution capacity.

The post-2015 period saw a substantial expansion of centrally sponsored urban missions. Flagship programmes such as the Smart Cities Mission, AMRUT, Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban), and PMAY-Urban broadened the scope for intervention. Expenditure under the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs increased more than fourfold, from ₹201 billion in 2015-16 to ₹855 billion in 2026-27. Sanitation coverage improved significantly, and PMAY-U sanctioned 12.2 million housing units to address an estimated 19 million urban housing shortage. Under AMRUT, over 15,000 water supply and sewerage projects were approved, expanding infrastructure coverage across cities.

Yet larger allocations did not automatically resolve structural constraints. In several years, utilisation rates lagged budgeted outlays, reflecting capacity bottlenecks and procedural delays. The Smart Cities Mission, despite approving over 8,000 projects worth more than ₹1.6 trillion, faced implementation challenges related to land acquisition, procurement processes, and limited municipal staffing. Its area-based development model, often confined to a small fraction of the city’s area, also raised concerns about uneven spatial benefits.

These gaps reflect deeper institutional weaknesses such as fragmented governance structures, overlapping mandates across tiers of government, and limited fiscal autonomy at the municipal level. Without clearer institutional alignment, cities struggle to convert density into sustained productivity gains and agglomeration benefits.

Even in the 2025-26 Budget, the Centre’s revised expenditure under PMAY-U at ₹75 billion fell significantly short of the original outlay of ₹198 billion. There has also been limited visible progress on the ₹100 billion Urban Development Fund announced last year, which aimed to redevelop urban infrastructure in Indian cities.

Recent Union Budgets appear to reflect these lessons. Rather than launching new flagship urban missions, the emphasis has shifted toward enabling a framework for regional integration and investment. Proposals centred on economic regions, urban corridors, and improved regional connectivity signal a move toward metropolitan-scale planning rather than isolated project interventions.

Equally significant are the recommendations of the 16th Finance Commission, which envisage a substantial increase in transfers to urban local bodies over the 2026-31 award period. Urban bodies are projected to receive ₹3.56 trillion during this period, more than double the previous Commission’s allocations, marking a notable expansion of urban fiscal space. Unlike scheme-based funding tied to centrally designed missions, these transfers are formula-driven and predictable, enabling municipalities to plan multi-year investments aligned with local priorities.

Taken together, these developments suggest the contours of a more sustainable compact, one that emphasises predictable fiscal transfers, strengthened municipal capacity, improved own-source revenue mobilisation, and regional economic coordination. This represents a gradual shift from mission-centric policymaking toward a more fiscally grounded and structurally embedded approach.

For policy intent to translate into durable outcomes, clarity in the division of responsibilities across levels of government is essential. Large-scale infrastructure, such as mass transit systems and regional mobility networks, may be most effectively planned and financed at the state or central level. Accountability for core urban services such as roads, water supply, sanitation, and local utilities, however, must rest with empowered and financially viable municipal governments. Local public goods require local accountability.

Urban reform, therefore, must extend beyond higher allocations. It requires enforceable reform timelines, outcome-linked fiscal transfers, metropolitan-level planning frameworks, and sustained investment in professional municipal capacity. Strengthening project preparation systems, improving revenue buoyancy through rational user charges and enhancing municipal creditworthiness.

Without such reforms, higher public spending risks creating fragmented assets rather than integrated, productive cities. If urbanisation is to become a durable driver of growth rather than a mounting fiscal liability, urban governance reform must be treated not as incremental adjustment but as a central pillar of India’s development strategy.