.png)

Venkat Thiagarajan is a currency market veteran.

January 27, 2026 at 4:36 AM IST

Imagine a turkey living on a farm. Every day, the farmer feeds it generously. For a number of days, the pattern holds. The turkey concludes: “This is life – safe, stable, predictable. The farmer always feeds me.” Then, the day before Thanksgiving arrives. For the turkey, it’s a shocking, catastrophic event. For the farmer, it was planned all along. This is the trap of false stability: what seems safest can actually hide the deepest vulnerability.

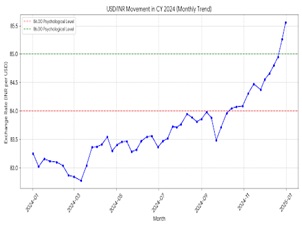

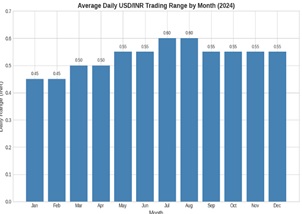

These analogies fit well with what has been happening in Indian foreign exchange markets. Just recall that in 2024, the pair traded in a steady range with very minor variance between 83.00–84.00 till November on account of the RBI’s dual-sided action. The central bank was the single largest participant in the forex market, buying and selling huge volumes on a daily basis and containing the trading range in the currency, creating a spectrum of stability.

The turkey in this case was the unhedged importers and foreign currency borrowers who assumed life to be stable, and hence there was excessive leverage in the system, and they came under the chop in 2025. So, simply speaking, the stability of 2024 gave rise to the fragility and volatility in 2025, which is extending into 2026.

There might be many valid reasons now to think that the rupee depreciation of this magnitude is not in consonance with the fundamentals, but the market is not willing to bet again on the basis of macroeconomic forces, which were never allowed to have any influence on the trajectory of the exchange rate not too long ago.

1. Markets always have the correct measure of the exchange rate; the central bank can delay the inevitable, not deny it

In theory, within a flexible system, central banks should leave the process of determining appropriate exchange rates to the currency markets. Supply and demand, and the reactions of currency traders to changes in the macroeconomic setting, result in the free-floating of exchange rates. In practice, however, central banks have frequently intervened to “manage” exchange rates according to their goals and priorities. As the current episode shows, it would be wise of the authorities to let the markets determine exchange-rate parity on their own, as markets have a way of asserting themselves.

It could be argued that markets might fail, which could lead to “wrong” exchange rates deviating more or less severely from the “right” ones. Consequently, central banks would have to intervene because they might have more and better knowledge than currency traders about the underlying economic fundamentals and their developments.

Whatever a “wrong” rate of exchange means, and however the “right” rate would be defined and measured, and ignoring the questions of why a central bank should have more and better information than market actors and why an intervention would be a better reaction than simply disseminating and sharing all of the relevant available information, history is replete with evidence that markets always have their way of determining the eventual exchange-rate parity, however hard central banks try.

Recall the heroic battle that the Swiss National Bank fought against the financial markets. It lasted 1,227 days. But in the end, in January 2015, an exhausted SNB finally capitulated and gave up its desperate fight for a weaker Swiss franc.

2. Impact of exchange-rate depreciation on the macroeconomy is always overestimated

The interrelationships between the financial and real sectors are very complex. Lacking clear guidance from empirical evidence, there is precious little consensus. The study of exchange rates is suffused with empirical “puzzles,” many of which suggest a disconnect between exchange rates and macroeconomic fundamentals that is hard to rationalise.

The “optimum” long-run real exchange rate is the rate that will efficiently channel production resources into industries that generate and diffuse productivity gains in the economy as a whole and that will thus tend to speed up and sustain the economic development process.

It has become conventional wisdom to assume that rupee depreciation of this magnitude has a contractionary effect on the real economy through its negative impact on firms’ investment spending. Simple textbook models imply that a depreciation is expansionary due to expenditure switching in goods markets. There is an equally strong argument that exchange rates are largely disconnected from other macroeconomic aggregates, and vice versa.

Overall, in the Indian context, historical experience shows that the exchange rate is much closer to asset prices than to macroeconomic fundamentals.

3. Positive impact of exchange-rate depreciation

On balance, episodes of depreciation and appreciation of the real exchange rate are beneficial for the economy in helping it attain domestic and external equilibrium.

A new equilibrium entails restoring potential employment and growth and resolving balance-of-payments gaps when there are changes in fundamental factors (such as productivity growth and demographic changes) and shocks of various types (such as terms of trade, commodity prices, and global financial crises).

Thus, depreciations can help prompt domestic growth. An exchange-rate depreciation, for instance, can achieve the same objective as a reduction of domestic prices in a large variety of goods and services.

In the face of exchange-rate fluctuations, it should be kept in mind that the real exchange rate is a relative price, whose flexibility and movement are essential to avoid large imbalances and distortions. To obtain this flexibility, the exchange rate, as a national currency price, can serve the function of coordinating a large set of individual prices in both labour and output markets.

In summary, the episode sends out the following messages:

- All participants, including the central bank, should accept a hard truth: perfect stability doesn’t exist. Absolute control only breeds hidden fragility. True stability comes from adaptability. And adaptability is forged in stress and small failures.

- Exchange rates and economies don’t thrive on rigidity. They thrive on fluctuations that preserve larger balance and encourage efficient allocation of capital by participants.

- The pursuit of flawless stability is an illusion – the “Turkey Illusion.” What we truly need is not control, but resilience. To have an efficient system, we must accept small doses of chaos, welcome uncertainty, and find certainty not in stillness, but in movement.

- Exchange rates are shock buffers and effective coordinating mechanisms, and both currency depreciations and appreciations are simply reflections of such flexibility.