.png)

Dr Hemachandra Padhan is an Assistant Professor, General Management and Economics, IIM Sambalpur.*

August 24, 2025 at 8:44 AM IST

Monetary policy has long been guided by the traditional trinity of price stability, economic growth, and financial stability. For decades, central banks relied on models that assumed shocks were temporary and that inflation could be steered by adjusting interest rates. But climate change has emerged as a new and complex disruptor, reshaping inflation patterns, undermining growth, and exposing hidden risks in financial systems.

For the Reserve Bank of India, the question is no longer whether climate change matters for monetary policy decisions—it clearly does. The challenge lies in how to integrate these risks into the framework without diluting the primary mandate of inflation control.

Inflation is the first and most visible channel through which climate change influences monetary policy. In India, where food carries nearly half the weight in the Consumer Price Index, weather anomalies can rapidly spill over into headline inflation.

Erratic monsoons, prolonged dry spells, and unseasonal rains have repeatedly disrupted food supplies in recent years. In 2024–25, headline inflation eased to 4.6%, the lowest since 2018–19, suggesting stability. Yet volatility persisted. Potato prices surged by 54% on average, while tomato prices doubled in major cities after supply disruptions caused by heavy rains. A similar pattern was observed during the 2023 tomato crisis, when prices spiked by over 400% in some regions.

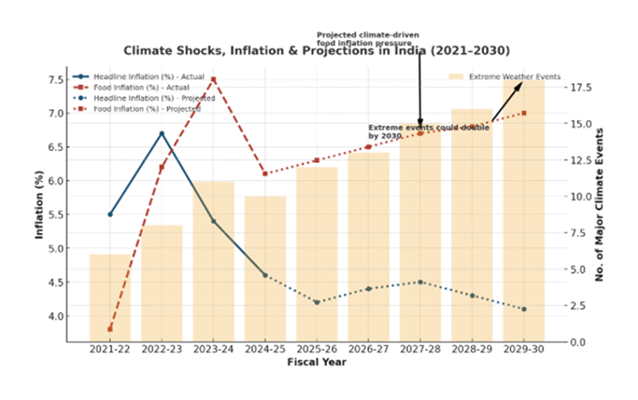

This is not an isolated occurrence. Data shows that food inflation has accelerated steadily from 3.8% in 2021–22, to 6.6% in 2022–23, and further to 7.5% in 2023–24. These figures reflect a structural shift, where climate shocks are no longer transitory but embedded in price dynamics. For a central bank with a 4% inflation target, separating temporary supply shocks from persistent price pressures is becoming increasingly difficult.

The danger is that repeated food price spikes risk becoming entrenched in household inflation expectations. If households expect higher food prices year after year due to weather uncertainty, wage demands may rise, fuelling broader inflation. In this sense, climate shocks are no longer a purely supply-side issue. They threaten to spill over into core inflation, which is the real concern for monetary policy.

*Author’s calculation.

Financial Stability Risks

Beyond inflation, climate change poses systemic risks to growth and financial stability. The Economic Survey 2024–25 estimates that India lost $87 billion to extreme weather events between 1990 and 2020. Agriculture, which still employs nearly half of India’s workforce, is highly vulnerable to rainfall variability, rising temperatures, and floods.

A single failed monsoon can slow rural demand, hit GDP growth, and reduce tax revenues. The risks are not limited to agriculture. Industry and services are also exposed. Extreme heatwaves disrupt labour productivity in manufacturing and construction, while floods damage transport networks, ports, and urban infrastructure.

The Mumbai floods of 2021 and the Chennai floods of 2023 both caused billions of rupees in economic losses, highlighting how climate shocks can cascade across supply chains. For the financial system, the risks are even more direct. Banks with large agricultural loan portfolios or exposure to real estate in flood-prone areas are at growing risk of defaults. Insurance companies face higher claims from crop losses and weather-related damages. International experience shows that climate shocks can quickly morph into financial crises. The Bank of England’s climate stress tests and the European Central Bank’s scenario modelling both highlight the need to integrate climate considerations into financial regulation.

Recognising this, the RBI in 2024 issued a draft Disclosure Framework on Climate-related Financial Risks. Under the proposed guidelines, banks will need to disclose their exposure to climate-sensitive sectors and conduct stress tests by 2027–28. This marks a crucial first step in aligning India’s financial sector with global standards under the Network for Greening the Financial System.

Looking ahead, the RBI projects headline inflation easing to 3.1% 2025–26 from average 4.6% in 2024–25, , aided by expectations of an above-normal monsoon and stable global commodity prices.

But such optimism is conditional.

Global climate models warn that weather volatility will intensify, increasing the frequency of droughts, floods, and cyclones. By 2030, India is projected to face nearly 18 major climate events annually, compared to just six in 2021–22.

Each of these events carries the potential to disrupt harvests, damage infrastructure, and trigger price spikes. The cumulative effect is a more volatile inflation trajectory, complicating the RBI’s ability to deliver on its 4% inflation mandate. Moreover, climate change threatens to erode the effectiveness of traditional monetary tools. Raising interest rates cannot bring down tomato prices caused by floods, nor can it restore supply chains disrupted by a cyclone.

This mismatch forces central banks into a dilemma: should they react to every climate-induced price spike, risking slower growth, or should they “look through” such shocks, risking credibility on inflation control?

Mandate vs. Reality

There is an active debate on whether central banks should directly incorporate climate change into their monetary policy decisions. Critics argue that climate mitigation is primarily the responsibility of governments, not central banks.

Fiscal policy, through subsidies, taxation, and investment in green infrastructure, is seen as better suited to address the root causes of climate change. Yet central banks cannot remain indifferent when climate shocks directly affect inflation and financial stability. The European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and the US Federal Reserve have already moved towards integrating climate risks into their policy frameworks.

The RBI, with India’s high dependence on climate-sensitive agriculture, has perhaps the strongest case to do the same. For India, the stakes are particularly high. Food accounts for nearly 50% of the CPI basket, compared to just 15–20% in advanced economies. This makes Indian inflation exceptionally vulnerable to climate variability. Ignoring this reality would weaken monetary policy credibility, as repeated food shocks could un-anchor inflation expectations.

The path forward requires a delicate balance. The RBI must remain focused on its inflation target while acknowledging that climate change is altering the very drivers of inflation and financial stability.

This will require:

- Integrating Climate into Forecast Models

- Strengthening Financial Resilience

- Coordinating with Fiscal Policy

Climate change is not a distant horizon risk; it is a present macroeconomic reality.

It is reshaping inflation dynamics, exposing growth vulnerabilities, and threatening financial stability. For the RBI, this means that monetary policy frameworks cannot remain static. In a warming world, the “cost of money” is increasingly intertwined with the “cost of climate”.

The coming decade will test whether central banks can adapt quickly enough. For India, where millions of livelihoods hinge on climate-sensitive agriculture, the integration of climate risks into monetary policy is not just prudent: it is imperative.

*Views are personal