.png)

India’s Deficit Promise Was Kept by Cutting Where It Hurts

The Centre met its deficit promise not through revenue strength, but by cutting transfers and development spend, shifting stress to states.

Rajesh Mahapatra, ex-Editor of PTI, has deep experience in political and economic journalism, shaping media coverage of key events.

February 1, 2026 at 11:53 AM IST

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has claimed a signal achievement. Five years after committing to bring India’s fiscal deficit below 4.5% of GDP by 2025-26, the latest budget numbers show the target was not only met but marginally bettered. The headline is tidy.

It is the arithmetic underlying it that is much less reassuring.

Revised estimates for 2025-26 show the fiscal deficit at 4.4% of GDP, unchanged from the budgeted ratio and lower in absolute terms. This has surprised public finance experts who had expected slippage after a year of weak tax collections. The surprise, though, lies not in any hidden buoyancy in revenues, but in the way the adjustment has been made.

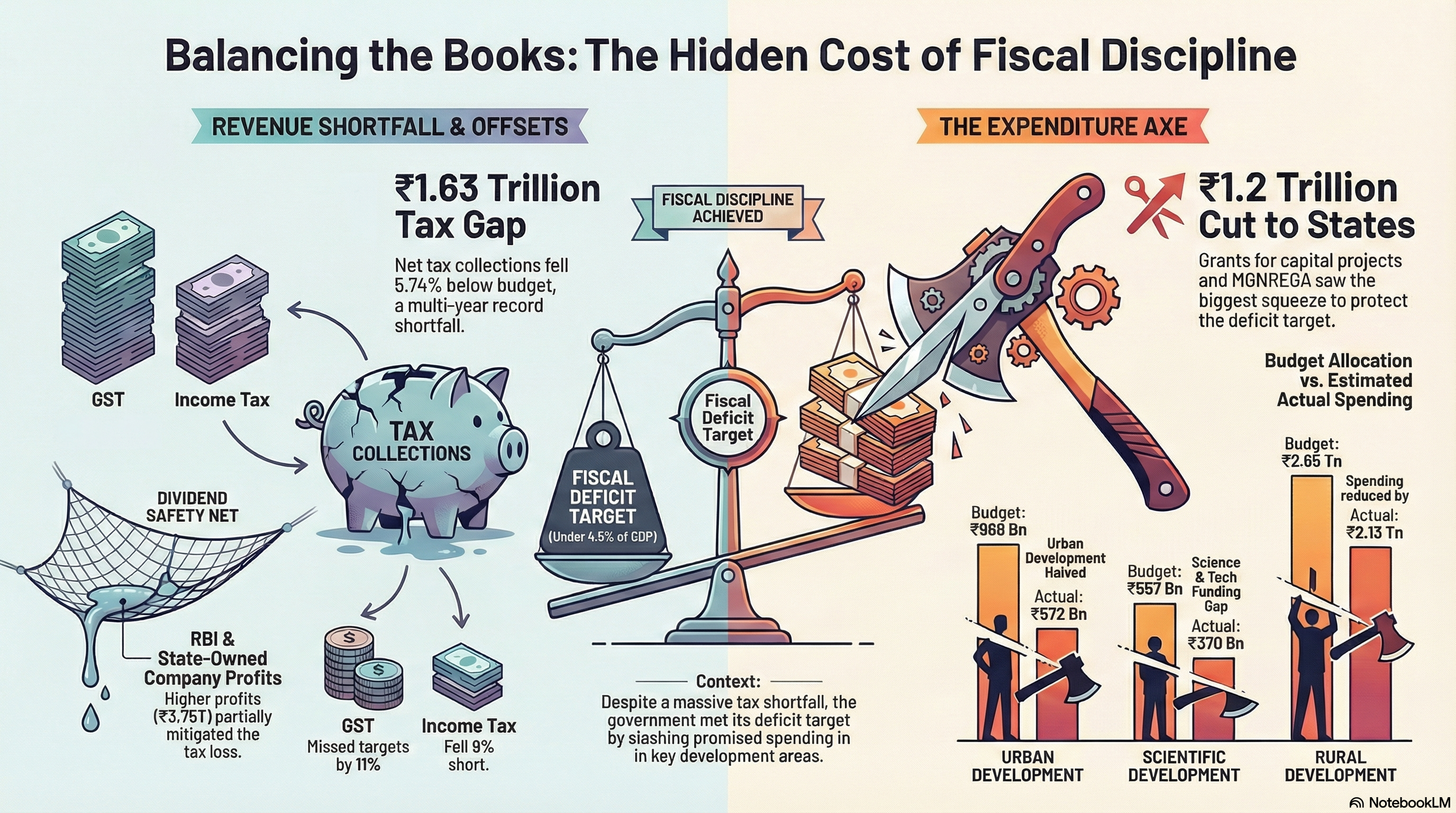

Start with the hole in the accounts. Net tax collections in 2025-26 are now estimated at ₹1.63 trillion, or 5.74%, below the budget target. A shortfall of this scale is rare in recent years, particularly outside crisis periods. The damage is concentrated where it matters most. Goods and services tax collections are estimated to be 11% below target, while personal income tax is short by about 9%. These are not peripheral levies but the backbone of the Centre’s revenue base.

Non-tax revenues have offered partial relief. Dividends and profits from state-owned enterprises and the Reserve Bank of India are now estimated at ₹3.75 trillion, compared with an initial budget estimate of ₹3.25 trillion. This windfall has cushioned the tax loss, though such inflows are inherently cyclical and cannot be relied upon year after year. Even after accounting for this, the revenue side alone could not have delivered the fiscal outcome the government wanted to showcase.

The decisive adjustment has therefore come from the expenditure side, and more specifically from selective compression rather than broad restraint. Capital expenditure, the category most closely watched by markets, has remained largely on track. That has helped preserve the narrative of a government committed to growth-supportive spending. The cuts have instead been concentrated in revenue expenditure and in transfers that are less visible in national headlines.

Double Engine?

This matters because grants for capital projects are among the most productive channels of public spending. They support infrastructure creation, crowd in private investment and strengthen sub-national balance sheets. Reducing these transfers may keep the Centre’s deficit in check, but it weakens the capacity of states to sustain growth and absorb shocks. The fiscal stress does not disappear. It is displaced.

A similar pattern is visible across several development-oriented heads. Spending on education, health and social welfare is expected to fall well short of budgeted allocations. Urban development spending is estimated at ₹572 billion, nearly half of the ₹968 billion originally provided for. This sits uneasily with repeated assertions by the finance minister, across successive budgets, that cities will be the engines of India’s future growth.

Rural development has not been spared either. Revised estimates put spending at ₹2.13 trillion, compared with a budget target of ₹2.65 trillion, a cut of about 20%. At a time when private consumption has shown uneven momentum and rural demand remains fragile, this retrenchment raises questions about the quality of the fiscal consolidation being attempted.

The sharpest contradiction appears in spending on science and research. The budget speech emphasised technology readiness, innovation and advances in science as central to India’s development strategy. Yet the numbers show spending on scientific development at just ₹370 billion, against a budgeted allocation of ₹557 billion. The gap is so wide that it cannot be explained by administrative delays alone. It reflects a revealed preference to defer long-gestation investments that do not yield immediate political or fiscal returns.

Not all spending has been curtailed. Expenditure on defence, police, administrative functions and subsidies for food and fertiliser is expected to exceed budgeted levels. These categories are politically sensitive and operationally hard to compress. The result is an uneven fiscal adjustment that protects headline stability while trimming areas that shape long-term capacity.

Judged narrowly, the finance minister has delivered on her promise. The fiscal deficit target has been met, and markets inclined to reward numerical discipline will take note. Yet fiscal credibility is not only about hitting ratios. It is also about the composition and sustainability of adjustment.

Consolidation achieved by postponing development spending and weakening state finances risks undermining the very growth that makes fiscal discipline possible. It buys short-term applause at the cost of medium-term capacity. India’s deficit has been kept under check, but largely in the margins, where the economic consequences are easiest to ignore and hardest to reverse.