.png)

Beyond the "Paracetamol" of PLI: How the Budget Can Rewrite India's Manufacturing Story

India needs structural reforms, not subsidies. This Budget must tackle energy, logistics, credit and the rupee to revive manufacturing.

Ajay Shankar is former Secretary of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Government of India.

January 30, 2026 at 8:51 AM IST

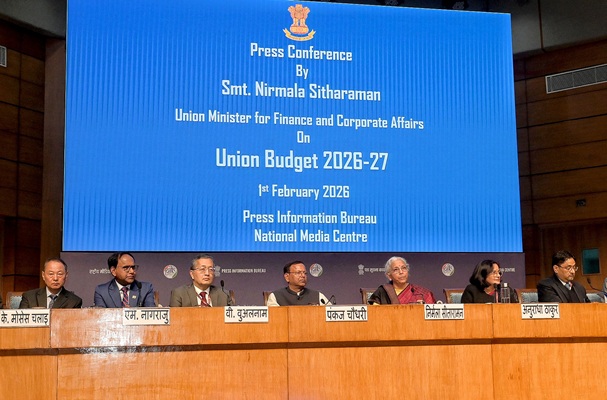

India stands at a critical juncture as Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman unveils the Union Budget for 2026-27 this Sunday. Despite various initiatives in recent years, the manufacturing sector remains a conundrum, with its share in the country’s GDP hovering around 15%.

The issues are deeply structural, which is why one would expect the finance minister to move past incrementalism and address the fundamental ailments of the sector.

The most significant barrier to manufacturing growth has been the high cost of production compared to competitors in Southeast Asia and China. While the government has focused on the soft part of reforms — ease of doing business, the underlying factors of production remain uncompetitive and unaddressed.

High Cost of Production

Logistics costs are inflated by high energy prices and inefficient transport modes. The Budget should initiate a roadmap to bring petrol and diesel under the Goods and Services Tax. Ideally, these should be taxed at lower or middle tiers because they are essential inputs for production.

Currently, the railways suffer from a cross-subsidy problem where high freight rates subsidise passenger travel. This makes railways—theoretically a cost-effective mode—unattractive for most businesses. The Budget needs to incentivise the creation of railway spurs directly to industrial plants to modernise cargo movement.

Power tariffs levied on industrial and commercial establishments in India are among the highest globally due to cross-subsidisation. Residential usage of electricity attracts relatively much lower rates. It is imperative that industrial electricity rates are decoupled from social subsidies.

Rapidly rising land values drive industrial units toward real estate development instead of production. The solution lies in state-led development of large industrial zones with social infrastructure.

The other major contributor to high cost of production has been the cost of credit. Interest rates are often multiples of what competitors pay due to financial market distortions. Despite many initiatives, including offer of interest subvention schemes from time to time, interest rates are often higher than what competitors in other parts of the world pay. Reforms to correct financial market distortions, therefore, should be a priority.

Bold Stance on Exchange Rate

A controversial but necessary move for the Finance Minister would be to signal a shift in exchange rate policy. Historically, India has allowed the rupee to remain overvalued, driven by a misplaced political belief that a strong currency reflects a strong economy.

In contrast, Japan, Korea, and China succeeded by keeping their exchange rates artificially depreciated to boost domestic value addition and exports. We should not be doing that, but we should also not try to prop up the rupee now that it seems to have corrected to the right levels.

The Budget should articulate a commitment to maintaining a competitive real exchange rate and preventing it from appreciating due to non-trade inflows like NRI remittances. This would provide a stronger business case for domestic manufacturing and help correct the trade imbalance with countries like China.

From PLI to Angel Investment

The current PLI scheme is like paracetamol — they treat the symptoms of high costs with subsidies but do not cure the underlying disease. Furthermore, many large corporations receiving PLI benefits might have invested regardless, while MSMEs continue to struggle with bureaucratic hurdles and rent-seeking at the working level.

The Budget should prioritise supporting domestic competition and helping small firms scale up through better access to land and credit, rather than just offering subsidies.

To be globally competitive, Indian firms need to invest big in research and development, but they often prefer buying technology from abroad rather than risking capital on domestic development. The Budget could propose that the state act as an angel investor for R&D, providing risk money for technology development. If the venture succeeds, the government could claim royalties on the IPR, similar to a startup investment model.

Navigating Global Geopolitics

The upcoming Budget must also contend with the "Trump shadow" and shifting global trade dynamics. As the world retreats from traditional globalisation, India must adopt a selective and calibrated approach to trade and tariffs.

Rather than shock therapy through across-the-board tariff hikes, the Finance Minister should focus on sectoral industrial policies. The success of Apple in India—which has demonstrated that global-scale manufacturing is possible in the country—serves as a blueprint for how strategic state support can yield dramatic results in a short period.

India possesses immense human capital, with a vast pool of talent ready for innovation, design, and shop-floor production. If the Budget can address the structural cost disadvantages and provide the strategic leadership seen in successful East Asian economies, the manufacturing sector can be turned around within three to five years.

(As told to Rajesh Mahapatra)