.png)

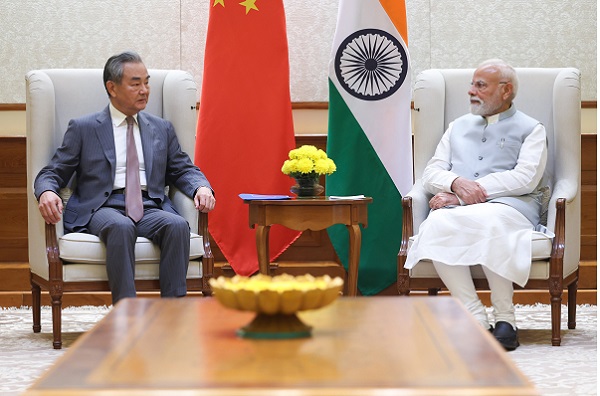

Between Washington And Beijing: India’s Search For Strategic Space

As Washington recalibrates and Beijing signals a thaw, India must weigh economic openings with China while navigating the shifting US–Russia dynamic

Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain is a former Commander of India’s Kashmir Corps and Chancellor of the Central University of Kashmir.

August 22, 2025 at 12:00 PM IST

China–India relations have always been defined by caution, mistrust, and the weight of history. The trauma of the 1962 war still lingers, while the clashes in the Galwan Valley in 2020 reinforced the perception that Beijing remains an unpredictable neighbour and strategic rival.

That confrontation, the worst in decades, pushed the two militaries into tense forward deployments across the Himalayas and led to economic retaliation, with Chinese tech firms restricted and apps banned. Yet paradoxically, India’s dependence on Chinese imports, from pharmaceutical ingredients to electronics, has only deepened since. This uneasy mix of hostility on the security front and entanglement in trade now defines the relationship.

The economic backdrop adds urgency. India’s growth, though strong in the long term, is slowing at a politically sensitive moment. Jobs remain the greatest challenge for a youthful electorate. China, despite being cast as the adversary, could offer partial relief. Targeted foreign direct investment in manufacturing could absorb India’s vast labour pool, create supply chain synergies, and help contain inflationary pressures. The brief “rapprochement” at the October 2024 BRICS summit hinted that both sides may be ready to explore limited re-engagement.

For New Delhi, this could mean cautiously allowing Chinese investment in specific sectors, even if full normalisation remains unlikely. The 2025 military stand-off with Pakistan reinforced India’s determination to avoid escalation on multiple fronts.

Still, the road to rapprochement is narrow. The Indian Army remains sceptical of China’s intentions, pointing to the unfinished disengagement process along the Line of Actual Control. The PLA continues infrastructure build-ups that preserve coercive leverage.

Meanwhile, the US under Donald Trump has revived its transactional instincts, pressing India not to deepen ties with China or Russia even as it flirts with its own uncertain course in Asia. Trump’s tariff threats underscore the limits of India’s leverage with the US. At home, public opinion toward China is overwhelmingly hostile, amplified by media that often veers into antagonism. The Belt and Road Initiative remains politically toxic in India, seen as a strategy of encirclement through projects in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. For these reasons, any thaw with Beijing is likely to remain tactical, partial, and vulnerable to shocks.

The structural balance is shifting. India is projected to grow faster than China in the coming decades, potentially becoming the world’s third-largest economy by the early 2030s. If this holds, Beijing could lose its traditional upper hand. For now, though, China still enjoys the advantage: as India’s largest source of imports and as a leading voice in the Global South through BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

India’s rise will not automatically translate into leverage unless it reduces dependence on Chinese supply chains. The paradox is clear: India may one day rival China in size, but on the way there it must still rely on Chinese goods and investment. Signs of rare earth deposits in India’s Northeast may offer some relief, but the gap remains large.

This delicate balance is further complicated by the United States and its Indo-Pacific strategy. For much of the past decade, Washington treated India as central to its counterbalancing of China, investing heavily in defence cooperation, intelligence-sharing, and the Quad alongside Japan and Australia. Yet recent signals suggest a recalibration.

As the US prioritises Pacific alliances with Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines, the “Indo” in the Indo-Pacific looks less central. Trump’s instincts lean toward selective deal-making with Beijing, and an eventual US–China rapprochement cannot be ruled out.

For India, this raises a difficult question. The dilemma is whether Washington now sees India as less central, or whether India’s unique geography and maritime power still guarantee it a pivotal role.

Russia remains the third element in India’s great-power calculus, often overshadowed by the sharper focus on Washington and Beijing. For decades, Moscow was New Delhi’s most trusted partner, the principal supplier of defence equipment, and a reliable diplomatic supporter in multilateral forums. Even today, a majority of India’s frontline military hardware has Russian origins, and energy cooperation continues despite Western sanctions.

The Ukraine war has complicated this equation by pushing Russia into a tighter embrace with China. Yet India has resisted Western pressure to downgrade its Moscow connection, choosing instead to maintain a delicate balance: importing discounted Russian oil, continuing defence cooperation, and keeping political dialogue alive. This is not nostalgia but hard realism. New Delhi cannot afford to jeopardise a partnership that underpins both its military readiness and its diplomatic flexibility.

In the context of a possible downturn in Indo–US ties, Russia may regain even greater salience. A fraying relationship with Washington would increase India’s need for diversified options, and Moscow, despite its closeness to Beijing, still offers a degree of strategic space. The challenge for India is to manage this triangle without drifting too close to Moscow or appearing to undercut its own Indo-Pacific partnerships. A difficult call that will test our diplomatic skills to a great extent.

The answer to India’s dilemma also lies in its maritime geography. From the chokepoint of Malacca to the Suez Canal, India remains the resident power most capable of providing net security to vital sea lanes. The Indo-Pacific is not just an abstract construct but a space where Indian naval reach is indispensable, whether to protect trade, deter piracy, or shape the flow of energy supplies. If India and China were to find a way of living with each other, managing disputes while cooperating in limited areas, this could prove awkward for the US. For the US establishment, the worst-case scenario is not hostility between India and China but the emergence of an understanding that sidelines American leverage. Even limited cooperation could be read as a threat to Washington’s role as the ultimate arbiter of Asian security. The irony is that India’s effort to preserve autonomy could be perceived by the US as a weakening of reliability.

The dilemma facing India is therefore sharp. Does it risk losing credibility by engaging Beijing more sincerely, or risk overdependence by tying itself closely to Washington? The answer may lie in hedging that maximises flexibility. India can cautiously test limited re-engagement with China while maintaining its robust US partnership. In practice, this means learning to live with contradictions: negotiating disengagement with the PLA while strengthening the Quad, accepting Chinese investment under scrutiny, keeping Russia engaged even as Moscow tilts toward Beijing, and managing public narratives that many times run more hostile than official policy.

It is this interplay between tactical necessity and strategic caution that defines the current “turn” in Sino–Indian relations, a complex shift that carries the danger of being misunderstood. From confrontation in 2020 to cautious engagement in 2024–25, the trajectory reflects neither reconciliation nor breakdown but a fragile equilibrium.

Beijing’s outreach reflects its desire to prevent India from sliding fully into Washington’s camp, while New Delhi’s caution reflects domestic constraints and the unresolved border. The million-dollar question is whether this equilibrium can hold.

If India manages growth and balances its partnerships, it can become the fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific. But if it leans too far toward Washington, depends too much on China, or neglects Russia, it risks being boxed into a secondary role. The coming years will test New Delhi’s skill — and decide whether India emerges as a decisive power in Asia’s future.