.png)

Dhananjay Sinha, CEO and Co-Head of Institutional Equities at Systematix Group, has over 25 years of experience in macroeconomics, strategy, and equity research. A prolific writer, Dhananjay is known for his data-driven views on markets, sectors, and cycles.

April 2, 2025 at 4:01 AM IST

India’s backdoor nationalisation of Vodafone Idea marks a fresh twist in the telecom saga. The government now owns 49% of the company, up from 22.6%, making it the largest shareholder. Billed as a life raft for the troubled operator, the move is better seen as a symptom of deeper structural rot in the sector—and the fiscal reckoning that lies ahead.

Vodafone Idea has long struggled under the weight of accumulated losses, falling market share, and an unsustainable debt pile. The company owed ₹ 2.03 trillion to the government, including deferred payment obligations towards spectrum (₹ 1.33 trillion) and Adjusted Gross Revenue (AGR, ₹ 0.7 trillion). Of this, ₹370 billion was due in the near term. Converting these into equity may offer breathing space, but it does little to fix the sector’s broken fundamentals.

This isn’t the first rescue attempt. A 2021 bailout had extended a four-year moratorium on dues and included a $2 billion debt-to-equity conversion plan for Vodafone Idea. That package was meant to offer room for revival and reform. As the moratorium nears its end in 2025, the latest conversion suggests that financial stress has not only persisted but deepened.

For the government, the implications go beyond corporate ownership. India’s budget relies heavily on non-tax revenue from telecom, especially from spectrum auctions. In 2024–25, the target from spectrum sales was ₹963.2 billion. The actual take? Barely 12% of that. Meanwhile, the revised estimate of total “other communication services” revenue is just ₹1.23 trillion—nowhere close to covering accumulated liabilities of over ₹4 trillion across the sector.

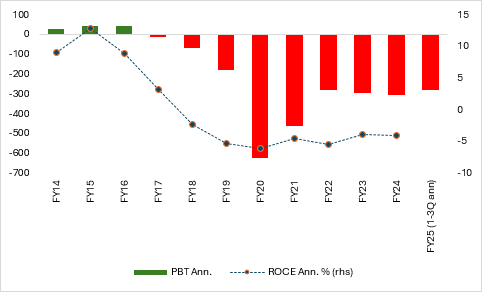

VI’s Profit Before Tax (INR billion)

In this light, the government’s equity acquisition in Vodafone Idea may also be seen as a fiscal compromise. What was once expected as cash inflow has now become an asset on paper. That undermines the budget math and raises the spectre of a larger fiscal deficit. Worse, if liabilities continue to mount, the state’s stake could rise even further, turning Vodafone Idea into a full-fledged public sector enterprise.

Is there a way out? Not under the current rules of the game. India’s telecom policy has long leaned on high spectrum pricing to pad non-tax revenues. These auctions, though counted as receipts for the government, are effectively debt taken on by telecom companies—most of it bank-funded. What looks like fiscal prudence is actually a deferred burden on the private sector’s balance sheets. It is a classic case of robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Over time, this model has driven consolidation. Smaller players exited or collapsed. What remains is a duopoly dominated by Reliance Jio and Bharti Airtel, collectively capturing 73.4% of the customer market share. Vodafone Idea, the lone weakling in this trio, having an 18% share, now faces an existential challenge. Competing in a capital-intensive business with a state as a reluctant and financially-stretched owner is hardly a recipe for success.

India’s telecom past does not inspire confidence either. Public sector players like MTNL and BSNL have seen value erosion, poor service quality, and slow innovation. The state has neither the nimbleness nor the appetite to run a competitive telecom operator.

None of this is to suggest that Vodafone Idea should have been allowed to fail outright. But propping it up without reforming the pricing structure, spectrum policy, and competition landscape is simply postponing the crisis. True revival would involve rationalising spectrum costs, offering clarity on AGR calculations, and creating space for new or revived competition—possibly even through well-capitalised niche players.

In the end, this hike in stake may buy time. It may even enable Vodafone Idea to bid for future spectrum or expand its network marginally. But as a transformational pivot, it falls short. Unless India ditches its reliance on telecom as a fiscal milch cow and shifts toward creating a truly viable competitive market, it risks repeating the same cycle of stress, bailout, and stagnation.